By Taylor Curry/El Inde

Starting Local

Growing up Latina in Tucson, Arizona, 19-year-old Rubí Rodríguez had been practicing mutual aid for years before learning the term as a discrete concept. For as long as she can remember, her friends, family, and neighbors have been sharing food, clothes, and other resources as a matter of practicality. Whether it was cooking and providing food for others or the exchange of hand-me-down clothes her community sought to provide for those in need in whatever ways they could.

For young Rubí’s family, sharing with the community and benefiting from that process was part of everyday life. “We realized that a lot of immigrant families, indigenous families, and marginalized families have been doing this for a long time with each other,” says Rubí. As a result of this learned experience, Rubí realized she can apply these skills she and her community have been practicing. This help comes in the form of assisting other marginalized communities that are struggling with material and financial resources.

Rubí has long dark hair with mild curls that frame her wayfarer style glasses. Rubí is a part of a small, Tucson-based, mutual aid and activism collective named After School Anarchy. As the oldest member of the group which is mainly made up of teenagers, Rubí has additional responsibilities such as managing finances or attending city council meetings. Despite having no formal organizing experience, Rubí and the other teens who are part of After School Anarchy are far from inexperienced when it comes to practicing mutual aid, community reliance, and self-sufficiency.

The group was started informally in March 2021 after students at a local high school began to collect unused and uneaten food items at lunch. After school, the group of students would try to distribute that food to people in need, in many cases, homeless people in central Tucson. As the group began to coalesce around the concept of mutual aid they began to expand their goals to collecting and distributing other resources such as clothes, school supplies, and hygiene products. They frequently participate in fundraisers for people and communities in need.

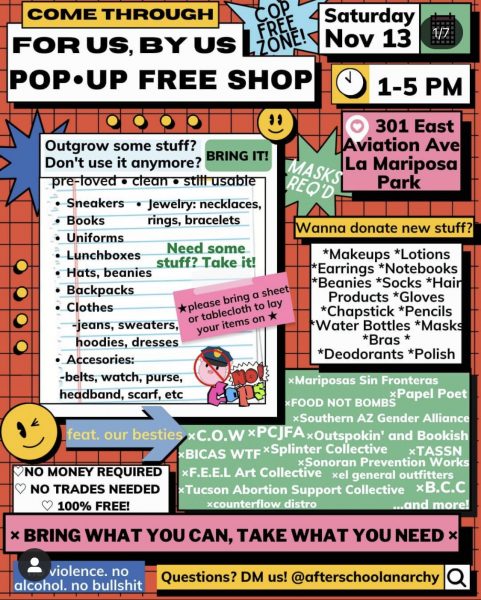

One such action the group takes to help those in need is their “free shop” program. These events, which they often hold at public parks, are opportunities for people to receive essential resources and materials at no cost. “There is a complete lack of requirements, so we don’t ask for ID, we don’t do a background check, we don’t ask,” says Rubí.

The program is targeted towards their fellow youths with some of the items being distributed being shoes, backpacks, lunchboxes, clothes and even watches and purses that were donated. A flier for one such event they posted on social media features the inviting line “Need some stuff? Take it!” In another event they collaborated with a group called Go With the Flow Arizona to distribute essential menstrual health items to people who may need them but cannot access them.

Systemic Deterioration

In the face of historical economic and social instability brought about by many factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, political turmoil, and the enduring legacy of racism and classism, there is an increasing gap between the needs of people and the ability of traditional government and state actors to address those needs in a timely manner. The cost of living is rising dramatically across the nation and especially in Tucson, AZ. which is exacerbated by a lack of sufficient support to help people keep their lives together.

To help alleviate these conditions, organizations and groups often engage in a practice called mutual aid. To practitioners of mutual aid, the act differs from the concept of charity in that mutual aid seeks to create a relationship of mutual support and cooperation that is a two-way exchange.

Traditionally, charity tends to be a one-way relationship in which the recipient is dependent on the charity provider. Mutual aid is a way of demonstrating community solidarity by helping to connect those in need to resources in the community.

Gradual Realization

The first thirteen years of my life took place in a typical majority white middle class neighborhood in the suburban sprawl of Portland, OR. I spent my youth living blissfully unaware of many of the harsher realities of modern American life. When the housing bubble popped my family did not lose our home and my parents did not lose their jobs.

It wasn’t until the 2016 presidential election, when I was a junior in high school, that I started to see the cracks in the facade that had been there all along, but even then I felt as if the current state of the union was an aberration rather than a trend.

Fast forward to 2020. I was at the peak of my college days when I began to see through the cracks. The COVID-19 pandemic replaced my relatively carefree life of friends, concerts, classes and parties with loneliness, anxiety, and depression. Later that year the murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement and the social reckoning that accompanied it helped me to reevaluate my understanding of the system we live under and participate in. The facade was crumbling fast.

Then in early January, the facade was gone and the house of cards was exposed to open air. As the MAGA rioters streamed their ransacking of the U.S. Capitol, I felt a sense of helplessness and hopelessness that was new to me. I spiralled for weeks until I found something that rekindled a semblance of hope for the future. I began to read about mutual aid organizations and the work they were doing in their communities. These people and groups weren’t waiting to be saved or for help to come from some three letter government agency. They were taking the mattress into their own hands and I found that profoundly inspiring.

I began to look around for groups I could join, to at least be a part of a larger network of people. My fear pertaining to a rightwing insurgency drove me to the Socialist Rifle Assocaition. A leftist organization advocating for firearms education and training. Through this ground I was encouraged to start gardening as well as learning about other local organizations. It was important to me to know that I wasn’t alone and there were many others in my community who felt the same way I did.

Looming Threats and Global Trends

In April 2021, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence in Washington, D.C. published a speculative report titled Global Trends 2040. The seventh edition in The Global Trends series, released every four years dating back to 1997, the report seeks to “provide an analytic framework for policymakers early in each administration as they craft national security strategy and navigate an uncertain future”. With this aim in mind the report gives a series of general predictions and trends relating to numerous topics ranging from political scenarios, impacts of climate change, and effects of new technology.

One of the trends noted is described as a shift toward adaptive approaches to governance in which outside actors will play a broader role in meeting the expectations of the public. This will be likely due to a decrease in traditional governmental structure’s ability to meet the growing needs of the public. This decrease can be partially attributed to a decrease in public faith in governmental structures, the ability of centralized governmental structures to project power, and an inability to address localized issues expediently.

The report goes on to say that “depending on the context and activity, non-state actors will complement, compete with, and in some cases replace the state.” These non-state actors as described in the report range from religious organizations, non-governmental organizations or NGOs, private sector companies, civil society groups, and criminal or insurgent networks. These types of organizations, despite their differences, have long played roles in the governance and organization of modern human society and have often stepped in to assume the role of government before.

These non-state actors are already present in the Tucson area. They can come in many forms such as business alliances, religious organizations and communities, local political parties, and mutual aid collectives. There are other more openly nefarious nonstate actors such as militant groups like the Oathkeepers, Proudboys, and other pseudo-paramilitary groups that will surely seek to gain legitimacy in the withdrawal of centralized state power.

Who Will Fill in the Gaps?

Certain groups are already well-positioned to fill this gap between public needs and expectations and who can adequately meet them. Large conglomerate corporations like Amazon and Facebook are already discussing and planning the creation of company towns that will be built, regulated, and governed by the company.

However problematic it may seem, this idea is far from untrodden ground and we only have to look to the past to see examples of this. Company towns have existed across the United States for centuries. In 1922, “nearly 80 percent of West Virginia miners lived in company houses.” In an era where the role of massive corporations in daily life has become increasingly personal, the prospect of Facebook or Amazon being in charge and writing the law may seem deeply unappealing to many people.

Other groups and organizations like extremist or authoritarian political factions may also capitalize on this shift away from traditional governance. A pattern of these groups stepping in in times of certainty has been observed throughout history from the rise of the Soviet Union in post-Tsarist Russia to the role Hamas plays in the repeatedly bombed-out Gaza Strip.

A recent example of this can be seen in Mexico where “Mexican criminal groups are clearly using the COVID-19 economic downturn and lockdowns to build up political capital by distributing handouts.” Despite the massive differences in the ideaology, shape, form, and function of these groups, they were able to take and hold power in part because of their ability to provide security, services, and resources to the public.

Organizations like Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación and the Sinaloa Cartel, which are famous internationally due to their utterly horrific use of violence, are able to gain goodwill in the communities they operate in or near by addressing their needs in a manner similar to how a government would.

In order to make space that is less vulnerable to the influence of such groups it is crucial that the needs and expectations of communities are sufficiently addressed. While the needs and expectations of communities go unmet there is space for malicious forces to do so and in turn gain power and influence in those communities. This is where the concept of mutual aid comes in. By practicing mutual aid, communities become more resilient and are increasingly able to address their own needs and expectations.

A Brief History of Mutual Aid

Pyotr Kropotkin was a political philosopher in Tsarist Russia who wrote on economic systems, community self-sufficiency, and hierarchy. In a collection of essays from the year 1902 titled Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution Kropotkin writes, “in the practice of mutual aid, which we can retrace to the earliest beginnings of evolution, we thus find the positive and undoubted origin of our ethical conceptions; and we can affirm that in the ethical progress of man, mutual support not mutual struggle, has had the leading part.” Kropokin theorized a system of economic organization based on voluntary mutual exchange and cooperation.

We do not have to look far back to 1902 to find examples of mutual aid in the United States. In the late 1960s, the Black Panther Party became known for its Free for Children Breakfast Program. The program was highly successful and fed thousands of children in many cities across the United States.

The program was so successful that the FBI took notice and became concerned. “The [Program] represents the best and most influential activity going for the BPP and, as such, is potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for,” wrote the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover in an internal memo.

Mutual Aid in the Age of Black Lives Matter, COVID, and Climate Change

More recently, mutual aid became a crucial component for community resilience in Portland, Oregon. Portland became famous for its particularly rowdy and prolonged series of protests lasting more than one hundred days. Throughout the protest movement, groups formed to address the needs of the protestors. These efforts took the form of communal kitchens, collections of resources such as personal protective equipment, and even legal assistance.

These groups also took a special focus on assisting the homeless population of downtown Portland who were affected by the protests. As the protests moved into more suburban areas, groups began to provide gas masks and respirators to families and people in nearby neighborhoods who were often being affected by the Portland Police Department’s extremely liberal use of tear gas.

This network grew continuously throughout the long period of protests until they were abruptly halted by massively destructive wildfires that ripped through the forests of Oregon and choked Portland and the Willamette Valley in a thick orange haze of smoke and soot. As evacuees from burning areas poured into Portland these mutual aid organizations stepped up to address their needs whenever possible. According to reporting by Al Jazeera, “the groups use multiple supply drop-off sites throughout the state, often in public parks or parking lots, and coordinate their efforts through a central hub staffed by volunteers.”

These organizations and groups were more or less completely made up of volunteers working long, hard hours to help those in need. People were not receiving adequate assistance from the state and those who stepped up to fill in the gaps were then systematically targeted by entities of state power. Effective mutual aid poses more threat to the status of the state than molotov throwing insurgents because mutual aid creates space in opposition to state power in which new ideas can emerge and become more powerful.

Addressing Issues Facing Tucson Communities

Tucson has its own mutual aid organizations and groups as well. The Blacklidge Community Collective describes itself as “a space for like-minded people who share a similar vision of the future.” The Blacklidge Community Collective is a space where several independent mutual aid projects are located. The groups that operate out of the BCC share a space because for these groups which have limited resources a physical meeting and gathering space is extremely valuable. One of the issues Rubí and her peers face is a lack of a physical space for organizing and collecting or storing resources. “We’re also a little anxious about not having one place to operate out of,” says Rubí.

One such project housed at the BCC is Tucson Food Share, a project of the organization Food Not Bombs Tucson. The goal of Tucson Food Share is to provide free vegan and vegetarian food to anyone in need, no questions asked. The group has a food pantry for those in need where they collect donations and collect materials. The group also offers a food delivery service where food is delivered to the homes of those in need who may not be able to leave their home.

Beyond the distribution of materials to those in need, Rubí and Afters School Anarchy have also begun to participate in local politics. Rubí and her peers attend city council meetings to help lobby their issues to the local government in the hopes that they might be encouraged to take action.

Like any city in the United States of America, Tucson faces many problems similar to Portland. Both cities are being severely affected by the changing climate and the COVID-19 pandemic and both cities have noticed a substantial rise in the homeless population. According to reporting from the Tucson Daily Star, “from 2019 to 2020 there was a 60% increase in unsheltered homeless people in Pima County.” While the percentage of unsheltered homeless people in Pima county remains relatively low compared to other large cities, this indicates that Tucsonans are increasingly feeling the pressure of the current state of the world.

Tucson is also a city with a poverty rate higher than the national average. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, around 22 percent of the population of the City of Tucson live below the poverty line. As supply chain shortages make the news on a weekly basis and once again stores are lacking important items such as toilet paper, the imperative for communal cooperation grows. This growing trend of mutual aid organizations and networks is a source of hope for many in an increasingly chaotic world. Rubí and her peers are working to be an active part of the solution to these problems rather than being a spectator.

After School Anarchy, the The Blacklidge Community collective, and Tucson Food Share are all small parts of the puzzle. The puzzle remains incomplete but as uncertainty grows, and the needs of the people continue to be unmet by the state, the community will begin to increasingly fill in that puzzle. Mutual aid isn’t an all encompassing solution for the problems the world faces. But it does offer solutions to a few key issues that will make addressing the bigger problems much less painful.