By Gabriella Cobian/El Inde

When Kristen Randall was 18 years old, she lived at home in Monticello, New York, and had recently graduated from high school.

A few months prior, Randall’s parents suspected she was sexually active and an altercation followed soon after in which her father hit her. She assumes her parents found out she was pregnant by reading a journal of hers. Randall wanted to have a conversation about her pregnancy with her parents and she only asked that her boyfriend is by her side.

But in the Spring of 2001, after she found out she was pregnant, her parents kicked her out of their home.

“I told them I was afraid of being alone with them because just a few months prior my dad had beat me up,” Randall said. “I wanted the safety of having my boyfriend there with me, but they didn’t want to talk to him. I got out of the car and said ‘Why don’t we go to a coffee shop and just talk about this?’ “They drove off and left me there.”

Randall lived in a tent for around a month while she was still pregnant before she was able to afford to live on her own. She scrubbed toilets at a nearby resort before landing a job at Burger King. She relocated to an old three-story Victorian home that was converted into multifamily housing. Her boyfriend was able to get her a space in the attic through a mutual friend who was willing to rent it for $350 a month without any security deposits. She has personally lived with housing insecurity for 8 years, until she was 26 years old, so she understands the anxiety many tenants face.

“When I was on the streets homeless I was pregnant, but after my son was born I vowed that he would never have to live that way,” Randall said. “I was in dangerous relationships at times and I’ve been in domestic abuse situations because at the time I felt like I didn’t have a choice.”

Randall moved into the quirky attic that had a toilet and bathtub shoved into a closet. By the time she was 22, she decided it was time for her to move near a university for a degree. She lived off-campus with her son and with the help of scholarships she was able to attend Binghamton University. As a full-time student, she got a job at Sears in the lawn and garden department while completing a paid internship with the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service for 16 hours a week.

Randall’s Chevy Corsica always failed. One day, she was pulled over by police and got a ticket for not passing her car inspection. She didn’t have $500 to get her car’s O2 sensor fixed, much less pay the ticket, so she had her license suspended.

One of the worst cars Randall ever drove was a Chevy Lumina that had no working heater. During sub-zero degrees in New York winters, she had to drive 20 minutes to get to work at a diner. Randall would have to sit on one hand and drive with the other hand since her hands would get so cold from the freezing temperatures.

Eventually, in 2009, Randall earned her degree in geology and environmental science at Binghamton University. She worked as an assistant database manager for the United States Geological Survey and then relocated to Tucson when a position opened up there. Once in Tucson, her politically active friends suggested she run for constable.

After some consideration, she finally sent in her application for constable hours before it closed in 2019. But before doing so, she spoke with former Pima County Supervisors Commissioner Richard Elias, and it was his speech over the phone that convinced Randall enough to leave her career at the Geological Survey.

Elias helped Randall realize that a constable can be more than just yelling at someone that they’re being evicted; it’s a position that can prevent people from eviction — the empathetic approach. Randall describes Elias as a man that could move mountains with only a few words.

“He was very poetic, he had a way of talking to people in a way that could draw them in and empathize with issues they never thought they should empathize with,” Randall said. “He was a great speaker and he loved giving speeches.”

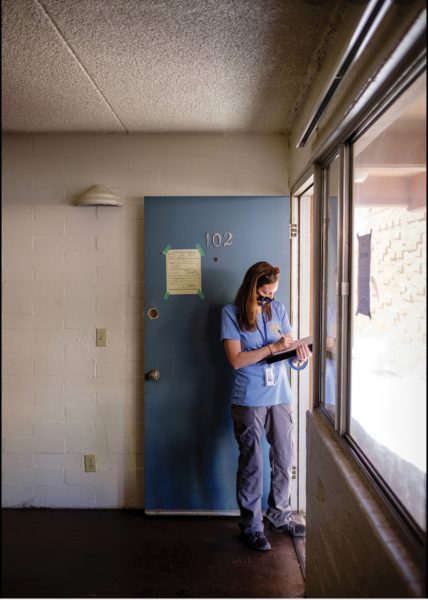

Randall was elected constable on Nov. 3, 2020. As part of her job, she wears a badge on her chest while holding eviction paperwork when evicting a tenant.

She says she follows two processes: the law process and the personal process. Her goal is to do all she can to keep tenants inside their homes rather than just showing up and evicting them.

“I love the ability to inject myself into the process, then make what would have been a bad outcome, a better one,” Randall said.

The straightforward approach of a constable is to send someone facing eviction an order in the mail, meet with the landlord — either knock on the door or open the door with a key — and then confront the people inside on eviction day. In this scenario, the protocol is for Randall to state that they have 10 minutes to pack up, leave and not come back, or it’s considered trespassing. This traditional eviction approach doesn’t take into account elderly or disabled people.

Randall considers herself the nerdiest constable in Pima County. Having worked extensively with data in her previous positions prepared her to track court filings and eviction numbers; science databases make it easier for her to query data within the unorganized system at the constable’s office. She considers her data expertise to be one of her most useful skills.

A now-retired constable also taught Randall to approach quietly, put the key and open the door instead of slam it open and yell “CONSTABLE! YOU’RE BEING EVICTED!” The routine was similar to what you’d see when a swat team barges into a house.

In one instance, Randall met with a University of Arizona student residing in a complex where the landlord had died. The landlord’s family took the steps to evict the student, and when Randall spoke with him, she heard extreme anxiety in his voice. He couldn’t believe his experience, since he expected guns and tactical gear.

When Randall goes to service an eviction she puts her foot by the door so the person opening it can’t close it all the way. Randall says it’s not uncommon to have people slam the door on her foot multiple times in an attempt to close it. Yet she maintains her composure throughout this entire ordeal, and she allows them to safely vent. According to Randall, her ego isn’t hurt when someone acts aggressively towards her because she understands these people are either scared or irate.

The harsh reality for Randall is seeing herself within particular evictions she’s confronted with. Factors such as low wages, huge bills, mental health crises, and domestic violence are all triggering for Randall. In addition to these factors, tenants have children just like Randall did. The majority of the time, she sees herself within the people she meets because of the same distress and issues she battled with.

“I wouldn’t do this job if it was just about showing up and evicting people,” Randall said. “I’ve made it my personal mission to try and make sure everybody gets a visit from me before their eviction to go over options.”

Randall goes out two to five days before an eviction to visit each evictee before the eviction day. She also carries a trifold eviction pamphlet: In case someone throws it away, she wants the first thing they see to be her name, her phone number, and approximate eviction date.

In it, there is a sample plan with lists of questions including rent and utility assistance, and contact information for a social worker for tenants to get their gears turning.

Forty-one-year-old Melissa Lucero faces financial instability and is on the verge of being homeless. Lucero is actively seeking financial assistance before she’s kicked out of her motel on 4th Ave and Benson Highway.

In an anxious tone, Lucero describes every day and night as a constant worry — she’s living with no money to her name. The difficulty in asking her two sisters and mother for financial support is knowing she can’t pay them back. When COVID-19 hit, she lost her job as a caregiver and was evicted from her triplex by her father in April of 2019. Lucero describes herself as the black sheep of her family, she doesn’t talk to her father anymore and is left out of family functions. Lucero is suffering from PTSD, depression, and bipolar disorder as her rent keeps rising.

She has constantly looked for apartments or trailers but they won’t accept her dogs: a Saint Bernard hound, a French bulldog bully, and a mixed dog from another litter. Although most people don’t understand, she considers her dogs her family and she refuses to leave them behind. She’s had them for 5 years and finds it difficult to find a home that will accept a larger dog like a Saint Bernard hound.

Lucero had been approved for Section 8, a federal housing program where tenants pay 30% of their income to landlords and the federal government pays the rest.

“I lost my Section 8 because of my dogs,” Lucero said. “I was homeless, no one would take me and my dogs, they’re all I have.”

According to Randall, tenants getting evicted often ask themselves, “What should I do with my pets?” So she provides emergency animal shelter information within her three-fold pamphlet. More often than not questions rise about pet assistance.

Currently, Lucero is living off of her Social Security benefits and Randall says the majority of people she deals with live solely off their social security. The problem is that the money typically doesn’t cover the rent nor other essentials they may need like food.

When someone answers the door for Randall she gives an eviction notice and has an open dialogue about what assistant they may need and what their plan is. By doing this, she’s kept many people in their homes simply for reaching out to them ahead of time.

Jorge Jacquez, an immigrant from Sonoyta, Sonora, a Mexican border town, spoke in his native Spanish. Jacquez relocated to Tucson in 1993. He’d been previously employed as a waiter at Las Cazuelitas, a Mexican food restaurant located at the Crystal Lake Plaza in Tucson.

Jacquez had a dispute with his landlord since his air conditioning and refrigerator stopped working at his apartment. He refused to pay the rent unless his apartment amenities were fixed. His food would rot each week the landlord refused to fix his refrigerator.

“Our landlord was annoyed, we told her we would leave once we found a place to stay, she refused,” Jacquez said. “She tried to evict us with the police but they explained that she had to evict us through court.”

The landlord took the steps to get Jacquez evicted through court soon after. Jacquez was able to stay in his apartment since the eviction moratorium was still in place. When the moratorium ended this past July 31, 2021, nothing was stopping the eviction from going through. Tenants were no longer protected from evictions. According to an article by the Arizona Daily Star, local rent has increased 7.1% from last year due to the growing demand and limited supply.

Jacquez was evicted from his apartment by his landlord and was granted two days to move all his belongings.

A better outcome for different situations is what Randall aims for. Randall aids in rental and housing assistance while mitigating any potential situations between tenants and landlords.

Around a year-and-a-half ago, Randall went to serve an eviction summons for a disabled tenant named Chuck who was in his 40s and paralyzed from the neck down. He had a colostomy bag and a caretaker that lived in the home with him.

Chuck was paying $300 a month for a small one-bedroom apartment and his landlord wanted to raise the rent. This particular eviction was not a non-payment eviction, Randall would find out, but the landlord had decided not to renew his lease and as a result, Chuck lost his court hearing.

According to Randall, shelters won’t take in people that aren’t self-sufficient. Chuck had complicated medical needs and special accommodations shelters aren’t equipped for.

During this time, Randall didn’t have a social worker to help her so she started calling the city, county, and every shelter she could think of without getting anywhere for a while. Randall understood that a market-rate apartment was nearly impossible for Chuck to afford, considering he had $750 a month from his Social Security disability benefits. Randall dug deep and found a nursing home that was willing to take Chuck in right away and draw up the paperwork.

Chuck declined the offer immediately when Randall mentioned it to him over the phone. He understood that if he went into this nursing home, he’d never leave it. According to Randall, the home would take all of his disability and give him a stipend of $20 a month. Chuck would never get the chance to save up money ever again and live on his own.

According to Randall, this experience helped the constable’s office realize the complexity of the situations they deal with. It sparked a relationship with the City of Tucson that led them to set aside a certain number of Section 8 vouchers specifically for the constable’s office. The eviction helped the relationship grow into programs and projects.

“We have to respect that these are people’s lives and they should have choices,” Randall said. “I wasn’t upset with him, I just dug deeper so I worked with the city and was able to find him an emergency Section 8 voucher. We found him a first-floor apartment that he and his caretaker could live in so now he has permanent housing.”