By Sam Burdette / El Inde

The afternoon of Feb. 28, Gene C. Reid Park’s Barnum Hill wasn’t the serene, tree-shaded grassy area it usually is. There were no families toting old bread for the ducks as they walked alongside the south pond’s rocky border, and there were no picnics on the gently sloping hill, which guides a small stream down to the pools on either side of it. That Sunday, this hill was not its usual quiet self. It was loud — and it was meant to be.

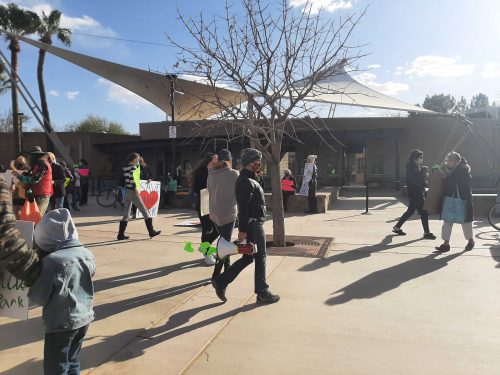

Circling the duck pond was a group of several dozen protesters, many dressed as colorful as the handmade signs of orange, green and pink they held. Every tree in the area was wrapped with plastic ribbons or adorned with cutout paper hearts, each with statements such as, “These trees are the lungs of Tucson,” and, “Only a heartless person would destroy a beloved park and cut down dozens of beautiful trees.”

These protesters are part of an organization called Save the Heart of Reid Park, co-founded by Tucson residents Wendy Sampson and Manon Getsi, who started the organization in November 2020 after they found out about the Reid Park Zoo’s upcoming plans.

“We’ve been bamboozled,” one bright neon sign stated.

This “bamboozlement” refers to the zoo’s expansion into the much larger and public Reid Park, a project members of Save the Heart of Reid Park have said they knew nothing about.

Photo by Sam Burdette/El Inde.

In 2017, voters passed an initiative for a small sales tax increase, the funds of which would go to the zoo for “capital improvements, operations and maintenance,” according to the city of Tucson ballot. The ballot does not mention the zoo’s plan to expand into Reid Park, a part of a plan zoo President and Chief Executive Officer Nancy Kluge said has been in development since 2014.

The zoo has a 10-year “master plan” made up of three phases, but it’s phase one that has some community members concerned. Save the Heart of Reid Park claims that voters would not have approved the initiative had the expansion been clear on the ballot.

While the city of Tucson and the zoo had already come to an agreement allowing the zoo to expand into the park, many Tucson residents were taken aback by the decision. Sometime in March, the zoo planned to begin construction on a new “Pathway to Asia” project, which will feature an interactive aviary, a reptile house and a new tiger exhibit, according to Kluge.

This expansion, however, will do away with public access to Barnum Hill and the south pond, repurposing the 3.5-acre area for a tiger exhibit, according to the zoo’s website. According to protesters, some will miss the shade of the trees, some the grassy hills, but others are just angry for being misled.

Getsi said she and other members of the group have been told they simply were not paying attention. In fact, the zoo’s website even says in reference to the Pathway to Asia project, “Zoo improvements were approved by voters in 2017 and project details have been discussed widely in council meetings, during more than 100 presentations with members of the community, and with local media.”

Getsi is adamant this is not just a case of ignorance.

“I work with my ward office, which is Ward 5, and have been for years about various issues,” Getsi said. “I mean, I’m not someone who doesn’t pay attention and neither are any of these other people.”

Photo by Sam Burdette/El Inde.

Getsi first found out about the plan “by accident” in November 2020 through the social media platform Nextdoor, where she began a conversation with others who were disconcerted with the city of Tucson’s decision, and the small group met together within the first week in one of their backyards, where they formed themselves into the organization Save the Heart of Reid Park.

What started as a small group of surrounding neighborhood residents has grown into an officially recognized nonprofit including members from all over Tucson, with its private Facebook page hosting over 1,400 members.

Emma Blake, a Save the Heart of Reid Park member, who bundled up in a puffy blue vest and a white hat for the protest, holding tightly to her sign, said, “I’m not anti-zoo, but I don’t understand why they’d take public green space.” Her dissatisfaction with the decision was heightened by the pandemic, as there were decreased opportunities for community members to safely leave their homes.

Blake said she would miss the tall trees, the water and the turtles. “This feels, like, a little more natural to me. … I like the messiness of it.”

Getsi also highlighted the trees and their shady canopy as her main reason she didn’t want to see this area of the park go.

That’s where those paper hearts come in: Many of the tall, old eucalyptus trees, whose bark is scarred beyond recognition with lovers’ initials, would be cut down. According to Getsi, the tall trees are especially important in Tucson with how hot it gets, and she says the smaller trees the zoo plans to plant, while there would be more of them total, won’t provide near the amount of shade and cooling power as the old trees do; it would take them many years to get to that point.

“This is a lose, lose, lose, lose situation,” Getsi said at the protest Feb. 28, speaking through a mic of the jazz band that played near the shore of the pond, whose music protesters had been dancing to. She announces then that the group will march across Reid Park to the gates of the zoo, and suggests chants.

The group slowly moves out, winding around the base of Barnum Hill, skirting the North Pond and then crossing the parking lot to congregate in the area outside the zoo. One family is just leaving the zoo as they arrive, and two policemen stand outside watching the group nonchalantly.

“Save the turtles, save the ducks,” Getsi shouts through her paper heart-adorned megaphone. The crowd repeats. “We hate your plan, it really sucks.” And the crowd repeats again.

After several minutes chanting various phrases calling for Barnum Hill and the South Pond to be saved, the group moved back toward Reid Park. A small band of two drums, a tuba and a melodica break out into improvisations as the group marches back.

Members of the organization and other protestors hoped their demonstration would be noticed by Tucson leadership. And they were.

On Wednesday, March 4, Tucson Mayor Regina Romero issued an executive order halting the zoo’s construction for 45 days from March 10.

“Throughout this last year, our experiences living through a global pandemic and quarantine has deepened the way our community values our public spaces and, especially, our parks,” Romero said in the statement, which was posted to the city of Tucson website. “I am calling for an immediate pause on this project and asking the Zoological Society, City administration and community stakeholders to come to the table in order to find a solution that works for all.”

The Reid Park situation is now center-stage on the city website as the first project featured in a list of scrolling pictures with descriptions. For this “community conversation,” as the city put it, they have created a timeline for finding input on the project, from collecting public comments to meetings between core stakeholders — a group including two representatives from Save the Heart of Reid Park — and the mayor and council’s final meeting, which is scheduled for May 4.

As the group of protesters arrives back at Barnum Hill, they file out along the edge of the pond again. Voices mingle with the continual quacks of ducks, and the wind sweeps through the branches of the trees above. The jazz band starts up again while the improvising band continues to play. It is loud once more.