By Emma Brocato/El Inde

Debbie Buecher is sitting on the patio of a coffee shop in central Tucson. On top of the small table sits her notebook, with the current page full of notes about the lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae) and its habitat needs.

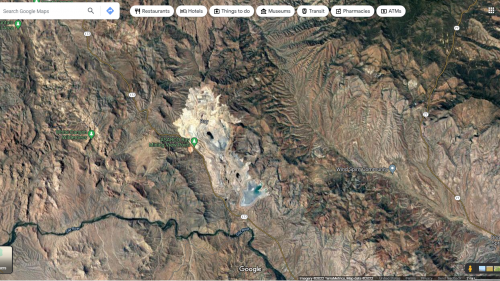

“When you drive down to Sonoita, there’ll be this big gaping hole next to you. Two thousand feet deep,” says Debbie Buecher, a bat scientist who runs Buecher Biological Consulting.

The hole Buecher is describing is a future pit associated with the proposed Rosemont Mine in the Santa Rita Mountains. The Santa Ritas are one of several mountain ranges collectively known as the Sky Islands of Southern Arizona. Nonprofit group Sky Island Alliance defines a sky island in this region as “a mountain that rises 3,000 feet (915m) in elevation or greater, has oak woodland habitat, and is isolated from surrounding mountain ranges by intervening lower elevation desert or grassland.”

The Santa Rita Mountains and surrounding grasslands provide habitat for a diverse variety of wildlife including the Mexican Spotted Owl and Montezuma Quail, according to the Audubon Society.

According to Sarah Truebe, habitat conservation manager with Sky Island Alliance, the area is an important migration corridor used by several species. Truebe says that if the proposed Rosemont Mine goes through, it will destroy habitats used by all wildlife in the area.

“We’re going from pristine oak woodland habitat to bare earth. Like that is…it’s gonna affect everything,” Truebe says.

In addition to completely removing all wildlife habitat in the area, this mine has the potential to be upsetting for humans and eliminate outdoor enjoyment opportunities.

“So its viewscape is going to be ruined. It’ll ruin birding in the area. It’ll ruin everything in the area,” says Buecher.

The company behind this controversial plan is Hudbay Minerals Inc., seeking to extract copper. According to the University of Arizona’s Superfund Research Center, during the process of open-pit copper mining, “a series of stepped benches are dug deeper and deeper into the earth over time,” followed by carrying out drilling and explosions to harvest large rocks. Similar to what happens with many other mine proposals, there has been public outrage from groups such as the Center for Biological Diversity.

On the Center for Biological Diversity’s webpage about the mine, they state that they have “been involved in multiple legal actions against the proposal.” They also discuss close to a dozen species that would be impacted by this proposed mine, such as the jaguar, which is endangered. They do not, however, discuss the lesser long-nosed bat.

The lesser long-nosed bat is currently receiving little to no media attention in relation to the proposed Rosemont Mine. This bat is not currently listed as endangered, but is an important pollinator species. But according to Buecher, it would be negatively affected by the mine.

“Rosemont Mine is sitting in fabulous agave habitat,” Buecher says. “So, for the many reasons people are against Rosemont Mine, that’s one of them. Because they’re gonna wipe out thousands of agaves.”

The agave plant is an important food source for lesser long-nosed bats, as they sip its nectar. Their pollination of agave and other plants is one way they serve their ecosystem. The lesser long-nosed bats have a roost two or three miles away from the Rosemont Mine property. They leave this roost and fly into the property to feed.

Buecher says it’s important to know that “agaves are not uniformly distributed,” meaning that one location could have significantly more agaves than another location in the area. She says that the proposed Rosemont Mine area having so many of these plants makes it an example of why agave surveys should be carried out prior to changing the land.

The mine will affect not only the bats’ food sources, but also where they will inhabit in some cases. Buecher recalls previously exploring some former mines in the area that had been abandoned by turn-of-the-century prospectors.

“And there’s some really significant bat roosts in those abandoned mines, which will just disappear,” Buecher says.

As someone who works for an environmental nonprofit with a significant focus on wildlife habitat, some of Truebe’s largest concerns about the Rosemont Mine are that it will affect such a large area of land, as well as the fact that the mining company is buying up private land to get past legal barriers to their activities.

In Truebe’s opinion, the proposed Rosemont Mine is simply not worth it. According to an article by AZ Central, the mine is aiming for roughly “5 billion pounds of copper.”

“The amount of copper that they’re looking at taking out of the Santa Ritas, it’s not economically viable,” she says. “It’s dumb, like they just shouldn’t do it. And they should put their money elsewhere.”

Truebe sees the proposed Rosemont Mine as a symptom of a larger problem: the global hunger for mining copper and other necessary resources. She laments wasteful consumerist habits and longs for a future in which technology products are built to last and be recycled, as opposed to “throwing away a phone every two years.”

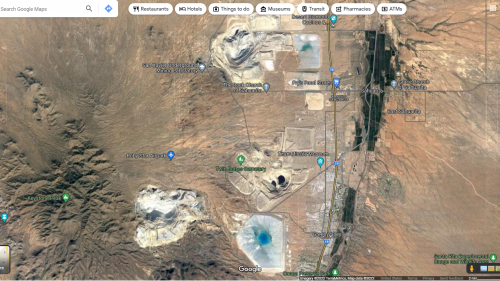

She also wants to see the industry shift towards more sustainable methods of mining, and away from the cost-effective open-pit method. She describes pulling up Google Maps with satellite view and being able to see mining pits from a bird’s eye view scattered around the state of Arizona.

“But I wish that we could find ways where we could protect these critical habitats, but also make it possible to mine,” Truebe says. “Because like, if they don’t mine here, they’re gonna mine somewhere else that’s probably critical habitat for something else.”

Truebe says that people should do more than simply care about environmental issues such as this – they should take actions such as contacting senators and donating to groups that are taking legal action against environmental threats.

In addition to the Center for Biological Diversity, another environmental group involved in opposition to the proposed Rosemont Mine is called Save the Scenic Santa Ritas. According to their website, Save the Scenic Santa Ritas is “working to protect the Santa Rita and Patagonia Mountains from environmental degradation caused by mining and mineral exploration activities.”

The challenges that will be created for the lesser long-nosed bat due to the Rosemont Mine echo global concerns for bats in general when it comes to open-pit mining. A 2020 study by Theobald et al in Acta chiropterologica states that “open pit mining reduces the activity of some bat species nearby, with negative impacts on species richness potentially extending up to 900 m[eters] from the mining activity.”

In a geographical region characterized by the Sky Islands, where a single mountain range can include several different types of ecosystems, the lesser long-nosed bat intends to sip nectar from agave plants. But if the Rosemont Mine goes through, these bats will have significantly less area in which to do so.