By Jake O’Rourke/El Inde

From the early 1990s to 2003, Linda Robles’ day job involved trimming roses of all colors, decorating vases to match and taking in the smells of pollen and petals at Roses & More. All that would change to bright lights and late nights in emergency rooms as her pregnant daughter Tianna suddenly became ill in 2003, forcing Robles to leave her job and focus her full attention on her.

“At that time, we just didn’t know what was going on,” Robles said. “She was in the intensive care unit from a reaction that she had when her symptoms became evident. After being in the hospital and ICU for about three months…Her kidneys were failing; a biopsy was done, and it came back that my daughter had lupus and nephrotic syndrome.”

Tianna was forced to deliver the baby early. In 2007, four years after her diagnosis, her symptoms continued to worsen, and she passed away at 19 years old. Her child was later diagnosed with temporary lupus, giving way to a series of heartbreaks as more members of Robles’ family were either born with birth defects or later diagnosed with lupus, brian cancer, and prostate cancer.

“In the 1980s, I heard about TCE contamination in my community,” Robles said, referring to trichloroethylene, a toxic solvent that was used from the 1950s through the 1980s to clean greasy and dirty metal parts on aircrafts and missiles at military sites. These chemicals were disposed of in open pits or washed into the ground, contaminating the soil and, ultimately, the groundwater. “When I would hear about TCE contamination in the news, I used to turn my TV off. I didn’t want my kids to hear about it because it was scary for all of us. It was a nightmare…I knew that my kids had been born with birth defects. But I was just so ignorant about the problem that I never even imagined to link it to their health…I thought it was me.”

Robles was raised in South Tucson, a mostly low-income, Latino community. In 2001, she moved northwest to the Midvale Park area, fearing she and her family had been long exposed to TCE-ladent water, which has been tied to long-term health consequences ranging from dizziness and blurred vision to more serious health conditions such as cervical cancer, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. But the move would not rid them of their problems.

In 2008, a year after Tianna’s death, Robles’ daughter Clarissa was diagnosed with lupus and permanent kidney failure. In 2009, her son Jojo was diagnosed with male lupus after living for years under the impression that he had syphilis. One in 10 people diagnosed with lupus are male and are more likely to experience problems with their kidneys, heart, lungs, and blood. Both of Robles’ children still live with chronic health conditions that seriously affect their daily lives.

Unsure as to what could be at the root of so many of her loved ones’ illnesses, Robles decided to go door to door to see if others were experiencing the same problems. She wound up with hundreds of statements from people in the South Tucson area who were reporting health conditions like lupus, lymphoma, leukemia, stomach cancer, colon cancer, and prostate cancer. Without digging into any research on this yet, Robles felt as though these illnesses were all connected to one source: the drinking water.

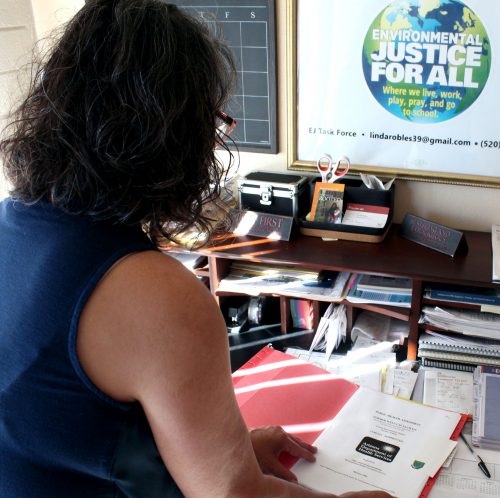

Photo by Jake O’Rourke.

In 2014, Robles started the community and volunteer group Mothers for Safe Air & Safe Water Force. She began to research, discovering another category of emerging chemical contaminants that was surfacing in sites around the nation: PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances). Referred to by scientists as “forever chemicals,” PFAS are a category of thousands of human-made chemicals used in the creation of myriad products ingrained in daily life. Food packaging, cosmetics, cookware, fire fighting foam, upholstery, and water- and oil-repellent clothing and surfaces are several examples of products historically made with PFAS.

PFAS have now been in use for almost 80 years. Once products made with PFAS break down, the nearly indestructible chemicals are left behind to leach into the soil, get into the air, and, similarly to TCE, contaminate groundwater. Thinking back to the ‘80s, when TCE contamination was discovered in the drinking water around the Tucson International Airport, Robles felt as though a similar trend was taking place again—and in the same community.

“That’s when I said enough is enough,” Robles said. She now resides in central Tucson; her apartment is cozy and tidy; her work desk has stacks of papers and letters she is currently reading or has already read. She pens hand-written letters to government officials pleading for change. “Unfortunately for people like our community, we’re predominantly Latino, low income, disadvantaged, underserved, populated community areas, and, unfortunately, we get left behind,” Robles said.

Her eyelids look heavy as she holds back tears. Her hands are tense, as she battles arthritis and degenerative disk disease. A tonsilectomy has left her voice in a rasp; it cracks with emotion when she speaks. Sitting at home alone, she flips through photos of her family members, those who are sick and those who have passed away.

In addition to what happened to Tianna, Clarissa, and Jojo, Robles’ grandson Emilio was born in 2009 with a cleft lip. Her daughter Yessenia was born in 1982 with a cleft palate, bone age delay, and a heart murmur. Robles noted that the severity of Yessenia’s cleft palate was irreparable, making it difficult on her speech and ability to find employment. She now works at a call center. Her nephew Eli passed away in 2015 from kidney cancer. She lost her niece Mia in 2017 to diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a rare and fatal brain tumor that forms at the base of a child’s brainstem. In 2019, Robles’ husband was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Without health insurance, they have been forced to pay out-of-pocket expenses for his medical treatment and monitoring.

Doctors cannot determine that PFAS and other chemical contaminants were the direct cause of her family’s illnesses, but research from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and national organizations is beginning to show that long-term exposure to PFAS can increase risks associated with cancer and various adverse health effects just as TCE had done decades ago.

“I cannot even tell you how difficult it was to live with sick children,” Robles said. “Spending most of my life in and out of hospitals. Seeing my little children be put to sleep for surgeries. When you’re in it, you’re not thinking; all you’re doing is just surviving…It hurts like hell to see your child sick, but all you can do is just keep on pressing.”

Through her continued grief, Robles has channeled her energy toward educating herself to make a difference for her family and her community. She wants to teach others about these toxic chemicals so they, in turn, can reduce their risk of exposure. In 2017, Robles’ research through Mothers for Safe Air & Safe Water Force led to the founding of Tucson’s Environmental Justice Task Force with the goal of informing the local Latino community while pressing local, state, and national officials to remediate contaminated groundwater sites and hold companies accountable for PFAS contamination. In 2017, Robles was invited to join the National PFAS Contamination Coalition, an organization that meets regularly with the EPA, the Department of Defense (DOD), and the Pentagon to discuss and advocate for PFAS remediation.

Strides have been made at the state and federal levels. Companies are curbing the use of PFAS, research is making inroads, and new technologies are being used at treatment facilities to clear PFAS from the water. However, having felt neglected for so long, Robles continues to encourage people in South Tucson to take matters into their own hands and find a voice to speak up.

“You can’t rely on the people that poison you to fix you,” Robles said. “That’s just the way I see it, and we’ve got to protect our health.” This past September, she showed up at the Scientists, Activists, and Families for Cancer-Free Environments (SAFE) EPA protest in Washington D.C. “Our children are getting sick and many are dying from environmental contamination,” reads the SAFE EPA protest website. “We are determined to make our case to EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan, the Biden Administration, and Congress.”

Robles doesn’t get paid for the work she does, yet, she is committed to continuing this work for as long as she is physically able to do it. “Public involvement is one of the key components to environmental justice, and without that, we can do really nothing,” Robles said. “Public involvement gives you a space at the table.” With her space secured, Robles uses her voice to speak for the hundreds of people she met going door to door in South Tucson, for the family members she has seen lose their lives to illnesses she believes were brought on by contaminated water, and for the coming generations so they might live in a safer environment than what is available now.

Through her hard work, and through the commitment of her fellow activists around the nation and the world, changes have been put into action. In 2016, the EPA announced a national health advisory level of 70 parts per trillion (ppt)—which can be equated to 70 droplets of water being added to an Olympic-sized swimming pool—for PFAS consumption and exposure. Anything higher than that threshold would be deemed unsafe. These new advisory levels meant that Tucson’s water treatment facility, the Tucson Airport Remediation Project (TARP), had to temporarily shut down because it was not able to remediate the water to 70 ppt. Federal money was put into place to reopen TARP with advanced technology for remediation, which previously served drinking water to 60,000 customers. Now the water is cleaned, recharged into Tucson’s Santa Cruz River, and no longer sent to homes to be consumed as drinking water.

With ongoing research, and with more stories starting to surface from individuals who have been affected, it is only a matter of time before PFAS contamination is publicly understood.

“We drank those chemicals for decades,” Robles said. “They’re in our bodies and they will persist in the environment forever.”

Through the rasp and cracks in her voice, Robles remains determined to be heard. Sitting at her desk in the corner of her apartment, she continues to pen a petition for more PFAS clean ups, breathing out the words she writes along the way: “change…action…now.”