By Mickaela Elich / El Inde

An orange pill bottle was slowly stripping away Bill Meeks’ life. As he sat in his hotel bed with no recollection of where he was, he realized that there needed to be a change. Meeks ended up in this situation when he was traveling the country 40 out of 50 weeks a year as an instructor for the International Association of Chiefs of Police for West Point Behavioral Sciences, based out of West Point, New York.

Beginning in high school, Meeks was extremely involved in physical activity. He was a four sport letterman and then went off to play football in college, which took a huge toll on his body. “By the time I got out of college, even though I was about 21 years old, I felt like I was about 51 years old,” said Meeks.

After college in 1979, Meeks started working with the Pima County Sheriff’s Department in the narcotics unit. Three years later, Meeks decided to leave the sheriff’s department after his partner was killed at the Ranch House Tavern in an undercover narcotics raid.

He thought his career with law enforcement was over and planned to move to the Pacific Northwest, though he decided to start doing police work again in Tacoma, Washington in 1983. A year later, Meeks was involved in a car wreck followed by a shooting range accident during police training.

After years of excessive pain following every one of his accidents, Meeks was given his first opioid prescription in 2008. As time went on, Meeks’ opioid prescriptions got progressively worse. It started with Vicodin, Percocet, Methadone, and eventually he was prescribed one of the strongest types of opioids, Fentanyl.

“As the opioid use would go up, my life would go down and I became more sedentary,” said Meeks. Dorothy, Bill’s wife, became increasingly concerned about Meeks’ use of opioids.

“He was not himself. His brain chemistry changed, he was not happy. He couldn’t smile. People would say “Why wont you smile” (and it was) because he was just in so much pain,” said Dorothy.

After retiring from active duty with the Tacoma Police Department, Meeks went on to teach leadership and police organization for the International Association for the Chief of Police. Because of how demanding travel was to teach these courses, Meeks was taking 300-500 milligrams of morphine every day.

This is when Meeks suddenly found himself sitting in a hotel room confused as to why he was there one day.

“I’d have to look at my phone to see what hotel I was in and where I was,” said Meeks.

That all changed when Meeks’ two sons came to pay him a visit from Washington. Medical marijuana had been legalized in both Washington and Arizona at the time, so the boys introduced the idea of trying medical marijuana instead of prescription painkillers.

Meeks had to laugh at the thought of even trying medical marijuana and told his children, “Seriously, boys, you know I put people in prison, seize their property, serve warrants. You know, that’s what we did and now you’re saying try this.”

Although Meeks was convinced medical marijuana was not for him, once he began to do the research, he became increasingly interested in learning about medical marijuana and its benefits.

After six long years of using opioids to cope with his pain, Meeks went into the doctors and asked to be taken off opioids and certified for a medical marijuana card.

Then Meeks went to his local dispensary in Oro Valley, Arizona, and got his first flower and started to experiment with the different strains available.

“I remember the first strain I got. I said I want the strongest stuff you got in here,” said Meeks.

The strain was called “Durban Poison” — a high energy sativa. As Meeks took his first couple of hits, he wasn’t sure if it was working or how to properly to smoke it. Yet while sitting in the car with his wife and two granddaughters, Meeks began to feel the effects of the marijuana.

“For the first time since 1984, I was out of pain for the three hours I smoked,” said Meeks.

Meeks spent days on end studying and understanding what cannabis is and how it worked. As time went on, Meeks was able to gradually stop taking prescription painkillers and switched to medical marijuana for his pain.

Over time, not only did Meeks notice a difference within himself, but also the people around him noticed as well.

“We didn’t come out of the closet so quickly and tell people what we were doing, but people started noticing, especially Bill. They noticed that he was changing and that he wasn’t falling asleep and drooling from the morphine anymore,” said Dorothy.

One day, Meeks was sitting in a dispensary looking around at everyone when he noticed something. “You know what they looked like? They looked like me,” said Meeks.

This was the first time Meeks and Dorothy ever envisioned creating a business that would coach people on how to properly use medical marijuana and how to be more effective with it.

Meeks’ business strictly started by word of mouth from certification doctors and dispensaries, but that all changed when an article by the Green Valley Sun featured Meeks’ cannabis coaching. For the next week, Meeks received close to 100 phone calls from people who had received their medical marijuana cards but didn’t know how to successfully use the plant.

Meeks’ ultimate goal in his cannabis coaching is to properly educate his clients on how to use cannabis and eventually allow them to be more independent.

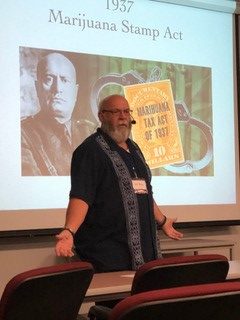

Within this last year, Meeks hasn’t only been teaching cooking classes on safe medical marijuana intake in 23 different states, but he has also taught a twelve-week course on cannabis’ medicine at the University of Arizona.

“We have gone from helping a couple of my friends and neighbors to now making an impact on not just the state, but a national perspective on how to use cannabis as medicine, not just recreational,” said Meeks.

Now that Arizona has passed Proposition 207 which decriminalizes the use of marijuana for adult use, Meeks says that those who may not have had access to marijuana because of legal restrictions are now able to try it for themselves without making a huge investment.

“We were at first against decriminalization,” said Meeks. But after so many people said they would try it but didn’t want to spend the money or get their license, they voted yes for the initiative.

In order to accommodate the growing demand for marijuana and its benefits, Meeks has tailored his coaching to those who want to try and use it as a form of medicine by offering a testing trial to evaluate the different dosages and forms of intake. He also hopes to create a cannabis education and processing center in every community where clients can come learn about the process or bring their medicine for preparation and dosages.

“It’s definitely a journey we didn’t expect to take. There have been some people that have not been as supportive as we hoped they’d be, but people are coming along. Even our leaders at church have been really impressed with how we’ve helped people, and they know we’re trying to do good for others,” says Dorothy.