By Vanessa Lucero/El Inde

Five-year-old Evelyn Jacobs, fascinated by her aunt Felicia’s fish tank in the living room while her mother and aunt continued their chit-chat in the kitchen, decided to keep herself busy. She grabbed the fish and laid them out on the table to feed them pieces of bread. Quietly causing mischief, her aunt came into the living room and didn’t know whether to laugh or cry at the scene in front of her. Unfortunately, after being out of the water for so long, the fish died, but Jacobs said her aunt most likely bought more fish because the tank was still around.

Memories like this fill houses from downtown Tucson before urban renewal in 1968. Jacobs’ mother was born in Hermosillo, Mexico, but her family was from a little town called Fabrica de Los Angeles. It used to have a factory where they would make clothes and send them to Los Angeles, close to San Miguel. Her father was born and raised in Tucson. His mother was the daughter of Leopold Carrillo, and they were nine kids. The first half grew up in the Sosa-Carillo house, but the others were born at another house known as “the big house.” Before urban renewal, Jacobs would go to the big house for gatherings and to hang out with kids in the neighborhood.

“It’s a sword with a double edge, where do you draw the line between good progress and sad progress? Because some progress is good,” said Jacobs.

The Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont house is a hidden gem still standing next to the Tucson Convention Center. It is officially registered in the National Register of Historic Places. It was saved due to its association with John Charles Fremont, who was the governor or Arizona’s territorial government. It was said that he stayed in the house, but according to records kept, it was his daughter who stayed in the house.

Alva Torres Bustamante became part of the Tucson Historic Preservation Committee and the Arizona Historical Society. Both groups came together to save the Sosa-Carrillo house and other places because of their historic value to the downtown Mexican-American community.

In the 1970’s, President Nixon’s wife, Pat Nixon, dedicated it as a historical site. There is a picture of this historical event at the Dunbar Activity Center.

“That is a political historical spot, with hopefully more to come in the future,” said Jacobs.

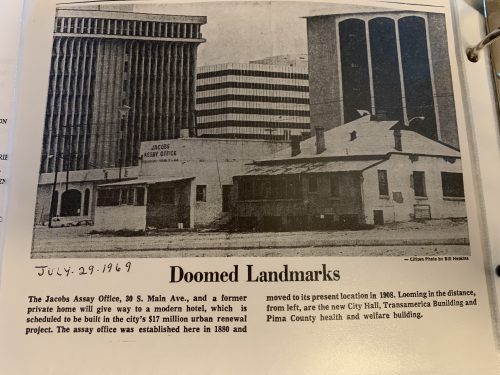

Another important historical site for Jacobs is the Jacobs Assay Office, replaced by a modern hotel. The only physical evidence left is the pane from her dad’s office which hangs at the Arizona Historical Museum. It used to be located north of the Sosa-Carrillo Fremont House.

Originally, the Sosa Carrillo house was made into row houses. Jacobs remembers playing with her cousins in the backyard on the fig tree that is over 100 years old.

Another important feature of the museum is the mirror at the entrance. It’s a huge diamond-cut mirror. People can hold the flashlight of their phone close to the mirror and they can see it sparkle.

“We hope in the future to make it more sustainable, to grow it as a museum and use it for quinceañeras, birthdays, weddings and that can sustain it enough so we can do exhibits,” said Jacobs.

Alisha Vasquez, co-director and volunteer, says that in the future she wants to focus more on what Tucson people wouldn’t think of. For example, the Chinese Chorizo Project, which is really about the mestizaje of the neighborhood. Chorizos would be found in many of the Chinese markets, leading to the creation of a Mexican-Chinese chorizo that was popular in the ’40s and ’50s.

“When we’re talking about the past… I am always so fascinated that we think the past was so long ago, but it really wasn’t,” said Vasquez.

This year, the first Tucson Chinese Chorizo Festival was held to commemorate the Chinese and Mexican immigration solidarity during the 1880-1960s. By the 1950s, an estimated 114 Chinese grocery stores were open for business. During the Great Depression, it strengthened their relationship as a community, helping the Mexican community buy on credit during difficult times. It’s a history that should never be forgotten and there are still people who remember how the barrio used to look.

Vasquez also has roots in Tucson, her great great grandfather used to own a carriage shop, where currently the DoubleTree hotel downtown sits.

“This place serves not only as a reminder of what was, but a continuation to celebrate the descendants of the people who make this place great,” said Vasquez.

Los Descendientes del Presidio de Tucson is housed in the Sosa-Carrillo Fremont House, and it was formed to help the descendants of families tell their stories. It is all volunteer-run. Betty Villegas, Raul Ramirez and Alisha Vasquez have been able to get grants to sustain the museum.

Los Descendientes gave birth to Las Doñas, women from the Tucson area who are movers and shakers and acknowledge their contributions to the history of Tucson. They now have become a non-profit organization themselves.

On December 9, 2022, the southern corner of the Tucson Convention Center will be dedicated to Alva Torres Bustamante, part of the Tucson Historic Preservation Committee and Arizona Historical Society, who joined others in trying to save the Sosa-Carrillo house and other places because of their historic value to the Mexican American community downtown.