By Patricia Schwartz / El Inde

Long before I met Alexander Soto in person, I knew him by his onstage persona: MC Liazon of the Phoenix-based hip hop group Shining Soul. I remembered seeing him rapping in a music video with the U.S.-Mexico border wall as a backdrop. In the video for the single “All Day,” he’s surrounded by other Indigenous and Chicanx artists and activists (though he prefers the term ‘concerned community members’) holding signs with messages like “No Ban on Stolen Land.” In the video, someone tagged his group’s name next to similar slogans on the concrete base supporting the metal bollards.

In another scene, Shining Soul is performing in front of a Border Patrol checkpoint on the sovereign Tohono O’odham (TO) nation, the reservation bordering both Arizona and Sonora, Mexico, where Soto was born. All of this was nothing more than a wire cattle fence when Soto was growing up in the 1990s.

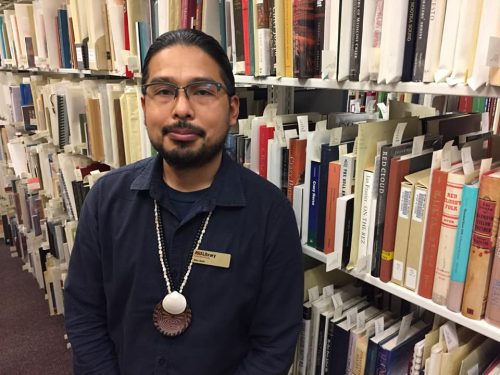

I met him this February in a different context — at The Fletcher Library at Arizona State University in Tempe. His unswerving and poised demeanor was easy to recognize, even behind his purple patterned mask. To his new position as a librarian and community archivist, he brings the same affinity for candid expression through storytelling which he uses to chronicle the evolving accounts of voices historically excluded from mainstream narratives in this country.

“I wear various hats, various shades of me. But foremost, I’m Tohono O’odham. With a dual background going between Phoenix and Sells, Arizona, and various O’odham villages back and forth my whole life, I’ve seen the changes,” he told me.

I had reached out to Soto to find out about his role in formalizing the ASU Library’s recent land acknowledgement statement — a task he has not taken lightly. I’ve noticed such statements appearing on email signatures and at the beginning of presentations with accelerating frequency. They’re already commonplace in other settler-colonialist states like Australia and New Zealand. Perhaps you’ve heard one: They’re typically a brief shout out to the original stewards of the land you’re standing on. Land which, no matter where you are on the North American continent, is the homeland of Indigenous peoples.

As land acknowledgements continue to gain prevalence in opening addresses and organizational ‘about’ pages, there remains much to discuss in terms of their impact for the communities they claim to recognize, and the responsibilities of the institutions touting them, like universities and libraries. Through both hip hop and archival work, Soto’s work probes what acknowledgement means to and for Native communities. And it plainly asks the critical question: What then?

Culture keeping, as he calls it, supports a slowly growing national acknowledgement movement, which is a step toward reconciling history.

As the Tohono O’odham nation must contend with its division by the foreign Mexico-U.S. border, relationships to land and land acknowledgment are particularly complex. Writing songs about his community’s experiences under border militarization involved compiling information he couldn’t find in other sources. According to Soto, “It was never really about trying to talk about it in this way that shows some ideology, some ‘ism or schism’ as I call it. It wasn’t because I’ve followed some activist’s narrative… It was always a matter of just sharing what grandma told me, what grandpa told me.”

From their own divided backyard, Soto’s family showed him how their homelands have steadily been usurped by federal entities without regard to their legal sovereignty.

Recently, O’odham activists opposing the previous administration’s fortification of the border wall have gotten some national coverage, but their struggle to preserve connections between O’odham relatives living on either side of the 75-mile boundary didn’t start with the newest iteration of the wall. There are at least 17 O’odham villages left in what has been claimed as Mexico. Their residents are unable to visit sacred sites, family or participate in traditional community events as the region is subjected to intensifying military control, surveillance and destruction.

Long before earning a master’s degree in Library and Information Science or booking international tours with Shining Soul, Soto found inspiration and connection in local hip hop scenes.

“Rap can help you say the sh*t you can’t say, and do it in a way to get people’s attention… And because no one was saying it, as a young person hearing Public Enemy say ‘Fight the power’ or NWA, say, ‘F*ck the Police”… Why can’t you say, ‘F*ck the Border Patrol?’”

He still lowers his voice when he “cusses in the library,” though we seem to be the only people in the bright and spacious Fletcher building at ASU’s West Campus at 8 a.m. on a Friday. Soto and the student workers have plenty of primary materials in stacks to catalog, but visits to the special collections and scanning equipment at the Labriola National American Indian Data Center are by appointment only these days.

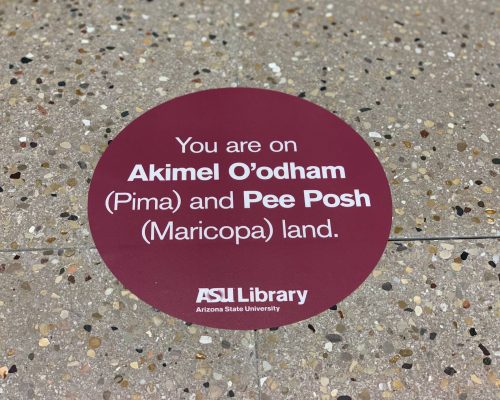

On my way up to the Center, I tread over stickers recently placed on the library floor — shortened versions of the land acknowledgement statement Soto helped craft for the institution.

workers. Photo courtesy of Labriola Center Social Media Page (Facebook).

They read: “You are on Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Pee Posh (Maricopa) Land”

Elizabeth Quiroga is one of the undergraduate employees who helped put them there. In general, she sees land acknowledgement statements as “stepping stones” to holding institutions accountable. In this case, she means it literally.

Quiroga is working on her bachelor’s degree in Social Justice and Human Rights. She’s Tohono O’odham as well, but hadn’t heard of Shining Soul, much less Labriola, until catching Soto’s presentation about the Center at an American Indian Student Services orientation event. She’s glad she decided to get involved. Being from a bigger city outside of the TO reservation, this is the first time and space Quiroga says she’s been able to “be involved so deeply with the Indigenous community.” She recounts that she didn’t feel Indigenous for most of her life, because she was never acknowledged as such.

Like most of the students who work at Labriola, Quiroga had never considered a career in Library Sciences. She’d started on a path towards law, wanting to make policy changes to combat ongoing encroachments on Indigenous lands and livelihoods, particularly, what she’d seen happening along the border through the TO nation. She’s not certain where her path will take her, but each of the student workers have become passionate about how archival work can be applied to their broader goals. For Quiroga, working at Labriola has expanded her toolkit and approach to defending sovereignty. “Since archiving, I see how much it is important to even have a basis to be able to fight for that,” she explained.

Labriola’s third-floor window offers a striking view of Central Arizona’s South Mountains, Moahdak Do’ag. The rocky desert expanse is one of many culturally and historically significant sites for both O’odham and Piipaash peoples now under the control of city governments in the Phoenix metropolitan area. With centuries-long history in the region, the O’odham fought for decades against the expansion of the Loop 202 freeway that would tear through the mountain range and the Gila River Indian Community which borders southern Phoenix. The Tribe filed additional resolutions laying claim over the preserve, citing National Environmental Policy Act violations and administrative failure to honor its consultation requirements. The freeway connection — including the stretch which crosses through the Gila River reservation — was completed last year despite the protest from Indigenous communities.

This view of the mountain is another reminder, like the border wall, of the intrusion on Indigenous lives and lands that galvanizes Soto’s work.

In between tours and recording he and the other half of Shining Soul, Franco Habre, ran beatmaking and songwriting workshops with youth for years. They’d drive out to schools like Baboquivari High on the TO nation. Sometimes, they’d work with kids at their local libraries. Participants were empowered to pour their own experiences into songs, while the only content discouraged in the workshops were raps with ‘hater’ attitudes.

Soto says it was here that he began to understand the importance of community access to information as well as the means to document it. Now, he tells me, “You need ways to inform our community about the power of information, the power of our stories that need to be preserved and archived, because if we don’t do it, we get lost in the abyss.”

Preserving place-based knowledge of the Sonoran Desert is vital not only for O’odham communities. Practically speaking, it’s in the best interest of all residents. Grappling with unprecedented wildfires and prolonged droughts, land managers in the West are looking to ancestral skills and information to rescue settlements from environmental disasters.

This is obvious for Quiroga and other Indigenous folks: “We’ve been saying this since the slaughter of the buffalo,” she reminds me. But in her experience, vital environmental knowledge “won’t be heard or respected unless it’s written down.” She sees archives as a practical way to translate information for the sake of the land and our relationships to it.

Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Quiroga.

Writing and performing as MC Liazon has taken a backseat in the last few years as Soto finished his degree and became more involved in the library. Throughout grad school, he began to further appreciate the potential of archives as liberation tools. He also observed the abundance of work needed to make up for the paucity of archives managed by minoritized groups. He cited a report finding that less than 2% of archives in Arizona are maintained by Latinx, Black, Asian & Pacific Islander, Indigenous and/or LGBTQ communities — even though these populations make up almost half of the state’s population.

In terms of Indigenous collections, Soto explains, “when you look at the Natives that are in the archives, there’s a little more… But then, it’s mainly by white institutions painting a cowboy and Indian narrative about Indigenous peoples.”

Historically, there hasn’t been a lot of emphasis on who has their hands on Indigenous history collections. I learned from the Labriola team that archivists can choose to curate collections anonymously, thereby obstructing their biases. Feminist and post-structuralist thinking has more recently become concerned with the assumed objectivity of whiteness embedded in our institutional archives. But Indigenous historians have always prioritized attribution as a decisive part of the practice.

Quiroga explains that, when learning a song in the O’odham tradition, it is always prefaced with the identity of the songdreamer. Having the context of where and by whom the knowledge was received or dreamt explains a lot about the intricacies of its meaning. You can trace where this knowledge comes from. “Those are things I want to incorporate into archiving in a Western institution. Knowing how Indigenous people archive is so essential to the progress we want to make today,” Quiroga tells me. ‘Indigenizing’ in archives takes shape beyond what’s often been an abstract buzzword when such procedures are institutionalized.

The ASU Library established the Community-Driven Archives (CDA) program in 2017 as an effort to address apparent gaps. Soto now heads the team bringing archival resources to local Indigenous communities who seek them. They offer workshops, host scanning days and provide acid-free boxes to folks interested in adding pieces of their own family repositories to collections in their communities. Their work is that of “debunking” archiving — helping people realize that we’re all already archivists. The photos your grandparents might have in that box under the bed, for example, those are historical documents. Culture keeping is a personal process.

Both Soto’s archival work and songwriting serve the purpose of preserving community information, but also of bringing oft-evaded history into common conversation. His agreement to participate in drafting the Library’s land acknowledgement statement was based wholly on its already-demonstrated commitments to addressing the historical lack of Native input in memory institutions. His focus lies beyond the statement. Now that it’s written, he wonders how it can be used to “tackle these issues of reciprocity and accountability with how our tribes have been treated by these institutions.”

It’s easy enough to spot how a type of national amnesia obscures this fact. For one recent illustration, remember how pop star Jennifer Lopez nonchalantly sang ‘This Land is Your Land’ at the presidential inauguration for Joe Biden. While white liberals celebrated the song’s roots in the labor movement, the Indigenous Twitter community understandably disparaged its overtly colonialist message and erasure of historical genocide.

The inauguration ceremony did not feature a land acknowledgement statement. If it had, it might have mentioned its place on the ancestral lands of some dozen tribes, including the Anacostans (or Nacotchtank), Piscataway and Pamunkey people. After centuries of displacement, genocide and forced assimilation, most states that surround the capital (Maryland, Virginia or Pennsylvania) have no federally-recognized Native lands. Overall, Native territories have been completely annexed in about a third of the states in the US.

Arizona is one of the 35 that still formally recognizes sovereign Native territories through reservations. The City of Tempe, home to ASU’s main campus, has just elected its first Native councilmember, Doreen Garlid (Navajo) and passed an official land acknowledgment resolution. The statement recognizes its central Arizona location as “culturally affiliated with the O’Odham, Piipaash and their ancestors.”

Local Indigenous activists hope this means that the city will remember its commitment next time a situation like the Loop 202 development through the Moahdak Do’ag mountain range comes up for debate.

“A land statement is really a vision statement. And so this our vision to advocate for Indigenous knowledge and methodology,” Soto says. “In time — and this is where this gets into the management and strategic planning sides of it — you have to really break that down into policy points.”

Many universities have published acknowledgement statements. Activists suggest more concrete steps. The funds could be used to implement a better history curriculum, recruit and support Native students, or create partnerships with Tribal colleges.

Soto observes, “It’s one thing to just say it,” he says, “it’s another thing to put your money behind it.”

Some institutions have indeed begun to show interest in doing this. It’s a move that feels long overdue, especially considering that 52 of the country’s most prominent and historic universities were built from endowment monies extracted from seized Indigenous lands. Investigative reporting on the history of the Morrill Act in this process has only begun to surface in recent years.

ASU was not a land grant beneficiary. Those state spoils were given to the University of Arizona in Tucson, closer to Soto’s hometown and the Tohono O’odham nation. But ASU maintains a wealth of Indigenous primary materials. It’s well-known that historically, much of the Native records that ended up in academic annals were extracted without full consent.

The Labriola Center came to oversee ASU’s collection in 1993. It’s now rethinking how the memory trove is administered. Soto’s team is piloting a software to better manage culturally-sensitive knowledge in the archives ASU has amassed over its 136-year history. They’re working on going through the collection with the input of community members to determine what knowledge should be restricted or even repatriated entirely.

With such extensive tasks ahead of them, the Center still needs funding — not just acknowledgement — to expand. Soto says it could use more space, more resources, more Indigenous staff. With a bigger budget, Labriola and the CDA program could engage more students in upholding the Library’s acknowledgement statement. A part of Soto’s vision emphasizes making an Indigenous space in the ASU library for Akimel O’odham, Piipaash and all Native people.

Though she regards it a lifelong process now, Quiroga used to think that archiving was the task of “some old white person who’s worked at the library forever. They wear their Mickey Mouse gloves and they go through the history.”

She admits that until recently, she hadn’t thought much about it. “You grow up knowing that you’re not represented in history, but before I started working at Labriola I didn’t really connect it with archiving. What I want to say now is that every individual experience and story is essential to preserving Indigenous culture. In anthropology they pick token people as representative of all of a tribe’s experience and it’s just not true.”

As Labriola’s social media manager, Quiroga has spoken about popular platforms as dynamic digital archives. She credits the app Tik Tok for much of what she’s learned about the lived experiences of other BIPOC folks during a year of quarantine. She emphasizes the distinction in being able to learn directly from (as opposed to about) people minoritized by memory institutions. Young users are making Tik Tok’s algorithms work for them, carving out collaborative spaces within the public platform. “This is what can happen if we archive ourselves,” Qurioga insists.

Apropos of Labriola’s official community partnerships, the Pascua Yaqui, Salt River, White Mountain Apache and Hopi Tribes have taken advantage of the archiving program thus far. But I’m told to stay posted, that there are big things in motion. As for Shining Soul — Soto hopes to get back into the studio and on stage just as soon as he and the team finish cataloging the bottomless stacks of primary materials blanketing every surface of their library office.

Photo courtesy of Labriola Center Social Media Page (Facebook), Feb. 2021.