By David Benjamin Lex / El Inde

The line to meet with the Rebbe was as long as ever. Any time Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson would open his doors in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, NY to receive visitors, hundreds of people from all over the world would gather. Many were neatly dressed head to toe in black, waiting hours for just a few moments with the Rebbe. Hoping to receive a bit of his wisdom.

“To go see the Rebbe, it wasn’t a simple situation,” remembers Rabbi Lewkowicz. “Special times the Rebbe would make himself available to talk to people, and the lines were massive.”

Rabbi Philip Lewkowicz, known to all as Rabbi Billy, is now in constant motion. His hands punctuate his every sentence as he tells me the story of his singular meeting over a video call.

While Rabbi Billy recounts the meeting, he is transported back in time to New York, when his beard was still reddish brown. The sleeves of his white collared shirt are rolled up to his elbows and white tassels called Tzitzit hang down from his waist over black pants. A yarmulke sits atop the energetic 62-year-old’s crown, surrounded by a horseshoe of white hair, but most of his hair is now located on his chin. His beard is grey and white, long and wispy, and when he’s teaching it frames a near-constant smile, interrupted mostly by his stories.

Rabbi Billy has been an educator in the Tucson Jewish community for over 27 years, acting as the director of Judaic studies at Tucson Hebrew Academy, teaching at Congregation Bet Shalom, teaching after school at Hebrew High, and acting as Rabbi at the Foothills Shul at Bais Yael.

Before that, Rabbi Billy taught in Johannesburg for over a decade at Yeshivah College of South Africa and the King David School. He was also an assistant chaplain for Jewish soldiers in the South African Defense Force, and volunteered with Street-Wise, a program serving struggling youth in Johannesburg.

Through it all, he has always remembered the “brucha,” or blessing, he received from the Rebbe that guided him.

Rabbi Schneerson, called the Lubavitcher Rebbe and often just ‘the Rebbe,’ spoke at least seven languages, and his published teachings comprise hundreds of volumes. He was a pivotal figure in the over-200-year-old Orthodox Jewish movement known as Chabad-Lubavitch, which had settled in Brooklyn during WWII

Schneerson led Chabad through the second half of the 20th century and was instrumental in its expansion across the globe into one of the largest and most prominent Orthodox Jewish religious organizations in the world. During his lifetime and even now, there are some Orthodox Jews who believe him to be the messiah. Schneerson’s death in 1994 sent shockwaves through the Jewish community, and although the 92 year-old left no successor, he is still revered as the spiritual leader of Chabad.

Unsurprisingly, getting a meeting with Rabbi Schneerson was very difficult. At one time he had received public visitors bi-weekly, but when Rabbi Billy went to see him in June 1982, he was only accessible to the public for a few days before the holidays. Visitors would come to Schneerson with a Kvitel, a small note of prayer, in hopes of receiving his blessings.

“I managed to get a private audience with him,” says Rabbi Billy, “and I remember standing in line for about two or three hours and when I came in, it was right about one o’clock in the morning. I told him that I need to go back to South Africa, to help my father.”

Rabbi Billy had just become a Rabbi when his father was diagnosed with cancer and given three months to live. His mother had asked him to return to South Africa and help with his father’s business. So Rabbi Billy had to leave New York. Before he left, he came to Schneerson seeking a blessing for his father’s health and the success of the business.

“He gave me a long, beautiful stare and I felt his eyes penetrate right to my core, into my heart and soul,” says Rabbi Billy.

“The Rebbe looked at me and said, ‘Your father will have a ‘refuah sh’lema,’ which means your father will have a speedy recovery,” says Rabbi Billy, “and you need to teach children with a true love and a true kindness, he spoke the words in hebrew to me… ‘ahavat amitie’ which means a true love and a ‘chesed amitie,’ and a true kindness.”

I first met Rabbi Billy at the Tucson Jewish Community Center when I was in Kindergarten, sitting in a circle with other students on a carpeted floor and listening to him tell a story. I heard many of his stories over the years, he would often tell stories as part of prayer services, school assemblies and during the holidays, and they were always delivered with warmth and compassion.

Years ago, I listened as he told us a story about a king and his three sons. The king, unsure of who should succeed to the throne, decided to test his sons’ wits, and presented them with a challenge. Each of the sons was given a room and instructed to fill it.

The first son fills his room with apples, but when the king comes to inspect his work he points out the gaps left in-between. The second son fills his room with sand, but when the king opens the door to examine the room, the sand pours out of the open door. The third son, cleverest of the three brothers, places a single candle in his room and lights it.

The king enters the third son’s room and remarks that there is only a single candle and the room is still nearly empty. The son replies that he has filled the room with light and the delighted king names him his heir. Rabbi Billy says that just like a single candle can fill a room with light, a single good deed can drive away evil and fill the world with goodness.

When Rabbi Billy returned to South Africa after his meeting with Schneerson, he found his father in remarkably good health. “He was looking more than good, he was like I knew him to be. He was functioning, not like someone who’s passing away in two months’ time.”

When Rabbi Billy told his father about Schneerson’s brucha, he was deeply moved.

“My father’s face turned white, he said ‘that’s what you’re supposed to do, you must leave now, and go to a school… I’m going to be fine, he gave me a blessing and you got to do what you have to do.’ And I was surprised that my father had to work out what the Rebbe told me and not myself, you know? But he lived for another nine years, somebody who was supposed to pass away after two months, and I went to teach.”

At the Tucson Hebrew Academy, Rabbi Billy taught me Hebrew and the ethics of Judaism. At Hebrew High those studies continued. Since my graduation our families have remained close, and I have attended Passover Seder at his house multiple times. Rabbi Billy also often chaperones THA’s annual eighth-grade trip to Israel, and even celebrated his 60th birthday on one of the trips. For many young Jewish people in Tucson, Rabbi Billy has served a crucial role in informing their religious studies.

“He loves teaching,” says his wife, Ada Lewkowicz. “He loves teaching, like he can’t get enough of it. Loves teaching kids, like how do you do that?”

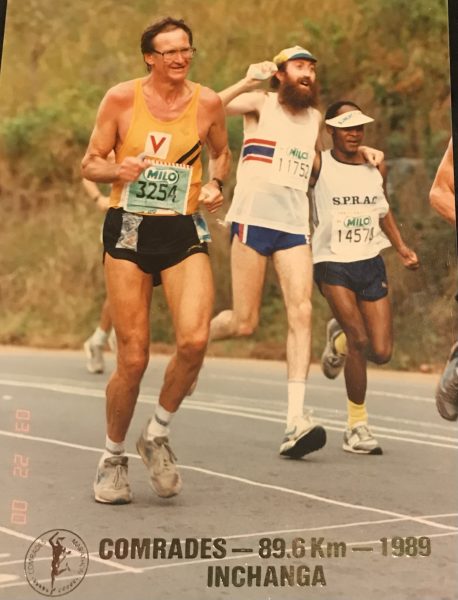

Rabbi Billy does it with ruach, with a spirit that has persisted since own education at a boy’s school in Pretoria, South Africa. Rabbi Billy joined the school’s track team and discovered a life-long love of running. Because of his energy he received the name Billy Whiz from friends in high school after doing well in a school mandated race.

“My hair, when I had hair, used to stick up with two coils in the air. It wouldn’t come down if I tried to put it down,” said Rabbi Billy. “If you look at the (1960s) comic character Billy Whiz, he had two pieces of hair that stuck up in the air like this, skinny and scrawny and ran all over the place, right? So they called me Billy Whiz.”

“It stayed from that afternoon, four o’clock, which was I think on a Tuesday afternoon, forty-seven years ago. The name came, it didn’t go away,” Remembers Rabbi Billy, “people took it so seriously that they put me in the school as Billy Whiz and they called my parents Mr. and Mrs. Whiz, very much to their discontent.”

Rabbi Billy looks back on those days fondly and says that his experiences in Pretoria Boy’s High School helped shape him into a stronger person, but he tells me that he had some issues with it as well. The school had a strict dress code and at that time schools employed corporal punishment such as caning to enforce the rules and keep order in the classroom. One day, after being told to cut his hair, Rabbi Billy was fed up.

“I was sent to the headmaster and he wanted to cane me six for questioning this hair story, and I told him ’You’ve got a master’s in education and all you’ve got, the only thing you can do is give me six cuts,” said Rabbi Billy. “It bothered me. What has my hair got to do with my education? What has my hair got to do with my ability [or] being a good student? It’s got nothing. Why are they telling me to cut my hair? They should be more worried about what I am, or what I’m struggling with, or what I’m not struggling with grades… Lo and behold this was one of the days my parents preferred to be called Mr. and Mrs. Whiz, because I was told to leave the school.”

It was not the only time that Rabbi Billy would struggle with authority. Growing up during apartheid, Rabbi Billy wrestled with the inequality that he saw every day on the street and even within his house. When he was 8 or 9 years old, he became upset that Philamon, a black live-in servant that he looked up to and respected, wouldn’t call him by his name but would only call him “boss.” Rabbi Billy recognized that there was something wrong and questioned his parents about the situation but was told that it was part of the culture. Black people and white people belonged to distinct social classes, and any blurring of that line was discouraged.

The apartheid system created a deep racial divide in South Africa and enforced a double standard that harshly punished any black people caught in the township without a passbook. Whites needed no such pass, and could travel the townships freely. Police patrolled neighborhoods and would employ batons called knobkerries to beat undocumented black people before dragging them away in police vans. The situation really troubled Rabbi Billy, who would go home feeling heartbroken.

Due to these discriminatory policing practices, Rabbi Billy’s mother and father often accompanied black servants on shopping trips and would check police stations if they went missing after traveling alone.

When he was 15 or 16, Rabbi Billy felt that he had to do something. Despite living in an affluent neighborhood, he found that there were other neighborhood teens who felt the same way.

“We said we’ve got to protest against this, and one day we did, and we moved to the center of town and we moved all the white-only benches. And we put them on fire,” said Rabbi Billy, “and we got big-time arrested.”

Rabbi Billy managed to avoid any major legal penalty, but for days afterwards, his father was silent.

“He didn’t talk to me. Oh, he gave me the silent treatment for about three days. I hated it because he was thinking, but I wasn’t sure what he’d do with me, and then one day in shul in the middle of the rabbi’s speech, he just leaned over to me with his face right into my ear and said, ‘If you want to protest, don’t become violent.’”

After that day in shul, Rabbi Billy says that he started to think differently about his life, about its meaning and about Judaism.

Rabbi Billy’s education and religious journey took a turn one weekend after attending a youth Shabbaton in Johannesburg. A Shabbaton is a weekend retreat with a focus on education, Torah study and prayer. Initially reluctant, Rabbi Billy’s apprehensions were eased talking with Rabbi Sholom Ber Groner. They ended up talking straight through the night, and Groner answered all of his questions perfectly, says Rabbi Billy. That weekend introduced Rabbi Billy to the philosophy behind Chabad and ignited a passion for education.

Chabad is an acronym representing the Hebrew words for wisdom, understanding, and knowledge: the values that represent the intellectual underpinnings of the Lubavitch Hasidic movement.

Chabad-Lubavitch has had an undeniable influence across the globe, managing a widespread outreach effort to build and strengthen Jewish communities and encouraging religious observance and adherence to tradition among secular Jews.

Chabad’s married emissary couples, called shluchim, operate almost 2,600 educational institutions in more than 100 countries. By the organization’s estimates, nearly one million children participated in Chabad activities in 1999.

By the time Rabbi Billy visited Israel with his parents and visited Yeshiva Kfar Chabad, he knew that he wanted to study Torah. He didn’t even want to return with his parents to South Africa at the end of the trip, and was so eager to begin that he began taking full-time classes, from eight until five every day, in order to finish his last two years of school in one.

While studying at Kfar Chabad, Rabbi Billy met a man whose influence shaped the way he approaches teaching and storytelling. Rabbi Menachem Mendel Futerfas, called Reb Mendel by his students, believed in the power of telling stories. Futerfas began teaching before 5 in the morning every day, and would end lessons with a story to capture the essence of the lesson.

Futerfas had been locked up in Siberia for over a decade for teaching and practicing Judaism in the USSR, and many of his stories were personal accounts from his time in gulags. A story can communicate ideas more clearly than any other medium, says Rabbi Billy, and Futerfas’ stories spoke volumes.

Futerfas told Rabbi Billy to keep a freezer of stories in his mind, and defrost them with warm words and enthusiasm. Rabbi Billy estimates that he tells as many as 300 stories a year.

After studying at Yeshiva Kfar Chabad for two years, Rabbi Billy knew he still had a lot to learn and so like so many other Jews at the time he went to Brooklyn, New York, to join the rapidly growing community of Orthodox Jews there.

It was an exciting time to be in Brooklyn, and Rabbi Billy was moved by the Rebbe’s devotion, his sincerity, and his infectious energy during the three years he lived there. Schneerson’s emphasis on teaching and building community resonated so deeply that thousands of adherents were inspired to venture out away from family and friends to establish Chabad Houses in foreign lands.

After returning to South Africa from Brooklyn, Rabbi Billy began teaching in Johannesburg, first at Yeshiva college and later at the King David School. While teaching at Yeshiva, he met his wife Ada.

“My aunt introduced us. She was teaching at the same school as him in South Africa, and she was describing him to me,” says Ada, “he would always be the one who gives the children the answers on the test.”

“I didn’t want them to fail.” Says Rabbi Billy “If they failed Judaism they’ll say they’re not a good Jew, so I would hate for them to fail Judaism. The point of a test wasn’t really to fail kids, it was to get them to know more.”

During an assembly one day in 1991 at the King David School, two doctors came in to speak, and asked for help and donations. Not for donations of money, but for donations of time and friendship.

The doctors were part of a community program called Street-Wise, which aimed to get impoverished black youths off the street and into school while at the same time fostering friendships across the deep racial divides in South Africa. Based out of a converted warehouse in Hillbrow, Johannesburg, black and white students participated in team-building cooperative games and exercises, such as charades, cooking, and making fashion shows from cardboard.

Rabbi Billy says that he was particularly proud of his involvement after a successful student peace rally at Rand University in 1993 attended by tens of thousands of people. Afterward, Street-Wise even received recognition from anti-apartheid leader and former president, Nelson Mandela.

In 1994, Rabbi Billy relocated with his family to Tucson, Arizona. After 12 years teaching in South Africa, a friend had told Rabbi Billy about the Tucson Hebrew Academy, a small school that was looking for a religious director. In Tucson he found a warm, welcoming community that he found difficult to leave, even when opportunities arose elsewhere.

Whether he is teaching during the week at the Tucson Hebrew Academy, on Sundays at Bet Shalom, leading a Sabbath prayer service at the Foothills shul or after school at Hebrew High, Rabbi Billy is driving his point home with a story.

Rabbi Billy has many stories, each of them with a moral. There are stories about light, stories about kindness, and stories about the value of knowledge and truth, and all are delivered quite rapidly in a warm South African accent. They are morals and values that show through in his life just as clearly as in his storytelling, rooted in a true love and kindness.

What a beautiful article. We are so fortunate that he has chosen Tucson as his home. Two of my grand daughters attend his Sunday school. Now I know why they adore him. What a blessing to have him in their young lives. I pray that they will take to heart the great wisdom that he has to share.