By Emma Peterson/El Inde

“Donna, how does this waffle look to you?”

“I think that looks pretty good,” she responded, examining the golden yellow morsel, still hot from the press. “It might be a little overcooked though, don’t you think?”

“That’s perfect, Poppa!” I said as I quickly spread butter in each of the honeycomb squares. My grandma looked at me, rolling her eyes and giggling in her special way. I could hear her voice saying “Oh, your Poppa can do no wrong, can he?” as she’s said before.

“This next batch is looking much better,” my poppa said as he lifted the handle to the waffle iron that sat precariously close to the edge of the kitchen island. He used his pinky to gently tap the hot waffles, and with a quick nod of approval, scooped them out of the iron and gently placed a waffle on each of our plates.

“I think these turned out perfect,” Grandma said. Me and my poppa both agreed with our mouths full. Poppa’s lemon curd waffles had always been my favorite, but this classic Belgian recipe had me second-guessing.

“Well, are you ready?” my poppa asked me as he got up to buss the dishes, only crumbs and melted butter remaining. I picked up my recorder and asked him the same. “Yeah boy,” he said, a classic Ken Reynolds response.

Grandma walked over to the sink to wash the dishes, but Poppa quickly caught her and offered to do it himself. Grandma assured him she was fine, and insisted he go sit with me and begin our discussion.

Poppa was always on his toes, ready to do everything he could to make life easier for my grandma. Their love and loyalty to one another has always been admirable to me.

I grabbed our coffees from the kitchen table and took them to the living room where my poppa and I sat facing each other.

“Alright, Poppa,” I began. “Just start from the beginning. Tell me the story of your life.”

Ken Reynolds was born in Wareham, England, a little city off the coast of the English Channel. His family was from Guernsey, a 25.1 square mile island between England and France, which was evacuated during World War II. In 1944, Reynolds’ mother, Dora “Mickey” Howard, met his father, Kenneth Reynolds, a military man. The two were married shortly after, dubbing Howard what was then known as a “war bride.”

Reynolds was born less than a year later, in 1945. “Needless to say, they wasted no time in having me,” Reynolds chuckled. When he was almost two, their family moved to the United States.

Reynold’s father, who participated in the Normandy landings and was involved in various European campaigns during the war, arrived wounded and sick. Most of his time in the United States was spent in and out of veterans’ hospitals, and in March of 1947, he passed away, leaving his young bride alone in a foreign country.

Widowed in her early twenties and unfamiliar with the customs of the United States, Reynolds’ mother sent two-year-old Reynolds to temporarily live with a family on a farm close by in Volny Center, NY while she endeavored to build a life in the States. But soon after, she fell in love and moved away, leaving Reynolds behind, and setting the foundation for what was to become an extremely difficult home life.

Reynolds’ mother was gone for approximately four-and-a-half years. In that time, Reynolds was raised by the Hubbard family as if he was their own. Reynolds recalls fitting right in on the Hubbards’ farm. “They cared for me, nurtured me, made sure I had everything I wanted, and made sure I went to school,” Reynolds said. He was the baby of the family, and subsequently received a lot of positive attention.

When Reynolds was six years old, his mother came back unexpectedly to claim him, accompanied by a new husband and a toddler son they called Freddie. They moved him five miles away from ‘Old Mother Hubbard,’ as Reynolds called his temporary mother, to their new home in Fulton, NY, although it felt like hundreds of miles away for young Reynolds. “I was traumatized that they wanted to take me from ‘Old Mother Hubbard,’ and over the years I came to realize I was way better off with her, as far as a loving, nurturing family.”

Reynolds’ new stepfather, Alfred Cavallaro, was a bitter man with a volatile temper. Around the time Reynolds turned 12, his mother and Cavallaro had another son named Danny Mike, who was born with leukemia and had Down Syndrome. “Back in those days, Mongoloid children, no matter how severe it was, and in his case, it wasn’t severe at all, were usually put in institutions,” Reynolds said.

His parents tried to raise Danny Mike for the first two years of his life, but he was unable to walk and screaming was his only form of communication, so they decided it was best for their own health to send him away. Reynolds, who was in his early teenage years at the time, understood what these institutions were like and visited Danny Mike often.

“It was a terrible, terrible place to be,” Reynolds said. “Mental health wasn’t treated how it is today. A lot of the children received lobotomies and other procedures that were approved by parents, which is sad knowing what we do today.”

One night, two years after he had been committed, Danny Mike got sick. Doctors at the institution attempted to bring fluids back into his body, but to no avail. Danny Mike died that night of “severe dehydration.”

“More than likely they just let him pass away, because there was nothing there to salvage in their eyes,” Reynolds said.

Just 16 at the time, Reynolds received the call that his brother had died. Meanwhile, his parents were nowhere to be found. “It was not uncommon for them to disappear three, four days at a time,” he said, “I couldn’t get ahold of them. I had the highway patrol looking for them, I had everybody looking for them.”

Unable to track his parents, it was Reynold’s responsibility to retrieve Danny Mike’s body and arrange the funeral. His mom and Cavallaro had apparently gone to New England and didn’t come home until three days after their son’s death. “It completely devastated me, devastated me,” Reynolds said, “I hated them, both of them.”

My poppa folded his hands and shook his foot like he usually does when he gets an itching emotion. I mostly see it when we play an intense game of “Sorry” or when we have a deep conversation about politics or religion over his fresh-baked brownies.

Grandma walked in after finishing the dishes and sat down in her chair by the window as Poppa continued to speak.

“So you don’t need to take notes, huh?” she leaned forward and asked me.

“I’m recording,” I quietly assured her and smiled.

My poppa abruptly halted his story and looked over at his wife with his sarcastically condescending eyes and quickly said, “Let me tell you about jumping in anytime you want to.” We all laughed, then Poppa continued.

Reynolds had a troubled home life with his mother and Cavallaro, who physically abused him. “You could say, ‘Was he drunk?’ No. I never saw the man drunk in my life, that I know of,” he said. “Just violent. He would lose his temper just like that,” he said while snapping his fingers.

In their bathroom, there was a hose that snapped into the bathtub by a nozzle that brought water through to the shower head. If Cavallaro saw the hose unhooked from the nozzle, even though it was simple to snap it back on, he would grab that hose and immediately start beating Reynolds with it, not caring who might have left it unhooked. After the beating, he would open his room window, letting in the freezing air and forcing Reynolds to do push-ups in front of it.

In the cold New York winters, Reynolds’ job was to shovel the sidewalk not only in front of the house he and his family were living in, but also the two houses that his parents were renting out next door. If his stepfather couldn’t see the grass peeping through the snow on each side of the sidewalk when he was finished, he would “beat the living hell out of you,” Reynolds said.

When he was in the eighth grade, Reynolds would often secretly steal Cavallaro’s car and gently push it back exactly to where it was parked before he was done. That is, until one day he was playing on a tree that he had climbed hundreds of times and suddenly fell 25 feet to the ground. Cavallaro had cut a limb off the tree he was in because he found out Reynolds had stolen the car the night before. “He sat there and said nothing. All he did was get up and go inside the house and lock the door. Needless to say, I didn’t steal the car no more after that,” Reynolds said.

It wasn’t until Reynolds’ junior year of high school that he finally fought back. Cavallaro had slapped him in a fit of rage over something so insignificant that Reynolds cannot recall what prompted his reaction.

“I had him pinned between two chairs, and he was getting ready to die. That’s when my mother pulled me off and told me, ‘Don’t hurt him!’ I think that was the last time he hit me,” Reynolds said. By this time, he had been involved in countless fights. Everyone knew high schooler Reynolds and the older kids he was involved with. No one ever dared to cross him, no matter their age or size. “I was a little guy, but if 10 guys were in my way, they would move so I could walk through,” he said. “I was the poster child for delinquency. I did anything I wanted to do. I answered to no one.”

Teenage Reynolds looked the part, too. “What you would do is get a pair of leather gloves that fit your hand really tight. You put little slices in the gloves and soak them in turpentine. So, when you hit someone in the face, those little slices you got in the gloves harden like razor blades. Not only did it cut their face, but it also stung like hell because of the turpentine,” Reynolds recalled. When someone tried to pick a fight with him, he considered the fight already won.

Reynolds’ best friend at the time was Teddy Knoll, the son of a mafia family. The Knolls controlled the steel painters’ union and the electricians’ union, where Reynolds later in life was able to get his little brother Freddie a job. The boys ran around together in a trouble-making crew, making a name for themselves in their small town of Fulton, NY. Reynolds felt a sense of power being best friends with the youngest of the five infamous “Knoll Brothers,” and it was part of the reason that no one messed with him.

“You thought you had a gentle grandfather, didn’t you?” Grandma laughed.

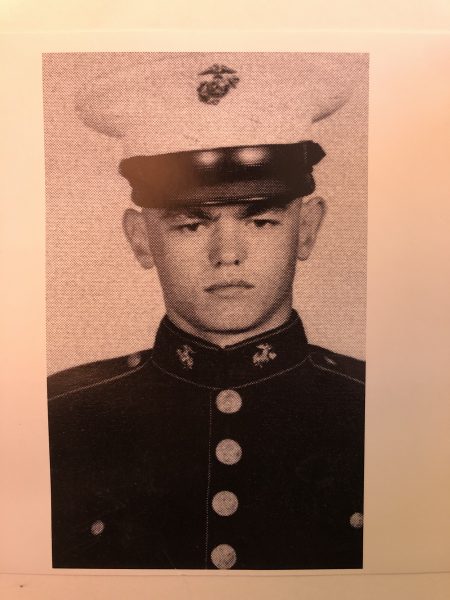

In 1962, Ken Reynolds takes a Marine profile photo in Parris Island, SC. Photo courtesy of the Reynolds family.

In 1962, at age 17, Reynolds realized his dream of enlisting in the Marine Corps, and he says it might have been the best decision of his life. He took a bus to Paris Island, South Carolina, where he began boot camp.

After 13 long weeks, Reynolds moved to advanced infantry training, where he learned how to shoot every firearm under the sun. Here he received some of the most intense training of his time in the Marine Corps. When he did something wrong, the drill instructors punished him, and when he did something right, they still “beat the living hell out of you.”

Despite the harshness of the training, Reynolds said it was nothing compared to the chastisings he would receive back at home. “Nobody actually grabbed you by the hair and beat you — it was more of a training tool,” he said.

After that, Reynolds moved to a base in Washington D.C. before being stationed in Cuba on the USS Boxer during the Cuban Missile Crisis. “All I knew at the time was just that we could get nuked at any moment,” he said.

Reynolds relished his time in the Marine Corps, but it was hard to ignore the broken home life he had waiting for him. He arrived home for the first time since joining the military to find his family had moved to an entirely different city without telling him.

“I knocked on the door of my home and this guy came to the door, and my first thought was that she must have dumped Cavallaro and hooked up with this guy,” Reynolds said. But the man told him he owned the house, and his mother and Cavallaro had sold the two houses next door, too.

He then contacted Ernie Nicoli, a mentor when he was in grade school who happened to be a cop and a detective. Nicoli told him Cavallaro moved to California, and his mother was in Phoenix, NY. His mother and Cavallaro had separated and later divorced. Reynolds hitchhiked all the way to Phoenix, where he searched for his mother and eventually found the bar where she was a regular.

The bartender told Reynolds where to find her. When he confronted his mother, she apologized by sending her son back to base with a box of “brand new” clothes, which he later learned were taken from Freddie’s closet.

In 1963, Reynolds was stationed in Washington D.C. during the assassination of President Kennedy. “We were some of the first people to know that the president had died,” he said. “One of our mottoes as Marines is that we ‘Guard the streets of heaven,’ and in this case, we guarded President Kennedy’s body at his funeral.”

One year after this impressionable time, Reynolds was sent to Guantanamo Bay on a helicopter attack carrier called the USS Okinawa. Meanwhile, the United States was about to enter the Vietnam War.

When Reynolds came back to his base in Washington D.C., he was stationed as a guard to make sure nothing and no one got in or out of the base without authorization. It was here that he met the future Mrs. Reynolds, Donna Hames, who worked in an office at the Navy Department.

Their first date was one to remember. They went to an intimate place called The Cellar Door in Georgetown to watch up-and-coming artist Joan Baez. “We were talking so loud that the bouncer came up to us and told us if we didn’t quiet down, we would have to leave,” Reynolds said. “We whispered, and he was watching us and would still come over and say that we weren’t supposed to be talking,” Mrs. Reynolds added.

Getting asked to leave The Cellar Door was only the beginning to their love story and the life they created together.

Hames came from a loving and protective home. Dating someone with such a dark past was new to her. “I knew he was a bad boy compared to all the other boys I’d dated, but I didn’t know how bad he was until much later. At eight years old, when he was sneaking out of the house, I was playing with baby dolls!”

Reynolds made rank very fast. In the last two years of his service, after marrying Hames at age 20 and her at 19, they moved to a base in South Carolina where Reynolds trained young Marines as a drill instructor. He gave lessons in booby traps, demolitions, firing weapons and taught young kids how to save lives. When the Vietnam War began, Reynolds moved up to sergeant status where these lessons became even more intense. Reynolds sent 1,200 men a week overseas, “about 30% of which wouldn’t come back” he said.

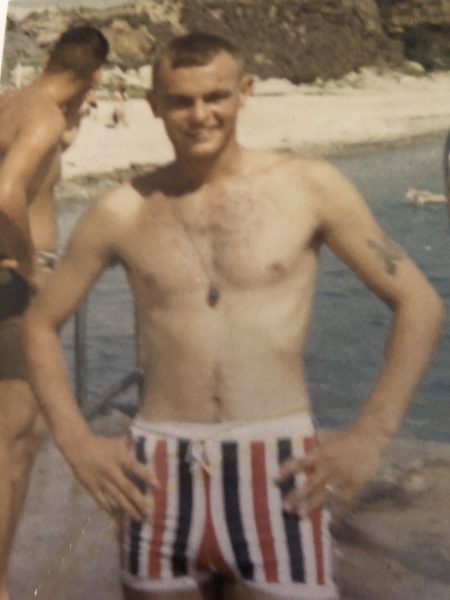

Shortly after Reynolds married Hames in 1965, he was sent to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, putting in mine fields. Photo courtesy

of the Reynolds family.

“At this time, I’m in my twenties, I’m still a kid,” Reynolds said. “I look back to 1962 when I was 17 and knew everything, but actually knew nothing, and I could see some kids going over there thinking they were invincible, and me knowing they really weren’t. I still look back and see some of those faces, especially the faces I later found out didn’t come back home.”

On a typical day at his Washington D.C. base in 1963, a year before his marriage to Hames, almost 19-year-old Reynolds received a letter from a woman by the name of Jaqueline Ray from Jordan, NY. His curiosity was piqued as he didn’t know of anyone from that city, though it was only about 10 miles from his childhood home.

He opened the envelope to reveal a letter and a picture that fell to the floor of a pretty, young woman. Reynolds’ friend picked up the picture and commented on her good looks, but his excited face shifted solemnly when he read the note on the back of the picture.

“Holy sh*t, man. You better read this,” Reynolds recalls him saying. Reynolds grabbed the picture from his friend and read the note on the back: “To my brother, whom I have never met.”

“Can I get you anything, hon?” my grandma asked me.

“How about a brownie?” Poppa interjected.

Sometimes I feel like I’ve gained ten pounds when I leave their house. Both Grandma and Poppa have a plethora of crave-worthy sweet and savory recipes. Grandma’s chicken and vegetable soup, Poppa’s salted caramel brownies; my mouth waters just thinking about them.

“No thank you, I am good!” I said, “I’m just going to grab a bottle of water real quick.”

I got up from the couch and walked through the kitchen to the garage. Every time I’m in that garage helping out Poppa or getting a drink from the fridge, I make sure to turn my head to the mural I created for them back in 2017.

As proud as I am of my creation that covers a whole section of their wall, it makes me even more happy to see how much my grandparents adore and brag about it every chance they get.

Hames and Reynolds get married in 1965 at a church in Washington, D.C.

Photo courtesy of the Reynolds family.

Jaqueline Ray was born two years after Reynolds. On arriving in the United States pregnant again, Reynolds’ mother had his younger sister in February of 1947. She was born with crippled feet and legs, unable to walk. When Reynolds was given away by his mother to the Hubbards, so too was Jaqueline with the promise that the couple she was given to would provide medical attention for her legs. Although the timeline and logistics of her adoption remain a mystery, Jaqueline was raised by the couple her mother sent her to. Meanwhile, Reynolds was given to a foster family which allowed his mother to take him back years later. His mother never told him he had a younger sister.

Jaqueline grew up knowing she was adopted, but Reynolds couldn’t help but wonder if he’d been adopted too. He knew little about his birth father, other than what was mentioned above. “Were the Hubbards my real parents?” he wondered. With so many questions, Reynolds asked his commanding officer if he could go investigate, which the commanding officer granted. Reynolds then borrowed a Marine friend’s car and drove straight to Jordan, NY. He asked everyone around town — mailmen, store owners, pedestrians — where his sister was. Eventually, he confronted and asked an old man he found in a neighborhood about Jacqueline Ray. The man’s eyes went wide before giving Reynolds an energetic hug. He was Jacquelyn’s adopted father.

He led Reynolds back to the home where Jacqueline was raised and waited for her to get home from school. When his 16-year-old sister first arrived home to meet her brother there was an overflow of emotions. It was a momentous and joyous reunion, but the longer Reynolds sat and listened to their explanations and stories, the more enraged he became. Why didn’t his mother ever tell him he had a sister?

The next day, Reynolds took Jacquelyn to meet her birth mother. “She said ‘Oh Ken! I didn’t know you were coming home. Who’s this? A new girlfriend?’ and I said, ‘Not really, this is your daughter,’” Reynolds chuckled. “I told her to get a good look, because this is the last time she was ever going to see me.”

He stormed out with his sister, who never formed a relationship with her birth mother thereafter. Reynolds kept in touch with his sister throughout the years and continues to today. He never truly forgave his mother, but chose to “tolerate” her years later.

Reynolds was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps after his six-year commitment in 1968. “The Marine Corps fit me perfectly. It fit my personality, I was structured, it was me,” Reynolds said.

“I think the Marine Corps saved his life,” Mrs. Reynolds said.

By the time he was discharged, Reynolds had a two-year-old son and a baby girl on the way. Like most young military families at the time, they didn’t have much and didn’t receive a lot of help. They were living paycheck to paycheck, which came in the form of $283, once a month.

“A big night out for us was the Sonic driveway,” Reynolds said. “We bought a room of furniture for $299, and we had it on a payment plan,” Mrs. Reynolds said, baffled at the price comparison of today’s amenities.

Reynolds never received a military pension from his birth father, despite being under the impression that his mother had been saving it for him for years. She and Cavallaro had spent it all on the two houses they rented out next door to Reynolds’ childhood home.

Being a veteran from the controversial Vietnam War made the young couple’s financial situation even worse. “It was a rough time. When the guys would get home and walk through the airport, people would boo and spit on them and call them ‘baby killers.’ It was terrible,” Mrs. Reynolds said.

“You’d go in an interview and the first thing they’d say to you was ‘Were you in the military?,’ and I’d say ‘Yeah,’ and they’d say, ‘We have nothing for you here,’” Reynolds said.

Without any financial support, a toddler, and a brand-new baby girl, Reynolds switched gears in his life and moved with his family to Indiana, Pennsylvania for a few years. “I worked two jobs just so I could pay for the delivery of my second child,” he said. For about two years, Reynolds lived off four hours of sleep to sustain his two fulltime jobs. It might not have seemed like it at the time, but eventually, all his hard work would pay off.

“I think there are many reasons he turned out so good,” Kelly Reynolds Peterson, Reynold’s youngest, said of her dad. “His faith in God brought him strength, guidance, and discipline. I think, similar to my grandma, Mickey, my dad saw it as having two choices: you either survive and succeed or you don’t. He’s a good example of choosing to survive and succeed, the difference between him and my grandma is that he’s a warm, loving person. Where he got that from, I’m not sure.”

Peterson remembers her dad being a hard worker, moving up the ladder quickly and always being liked by employers. Despite traveling often for work, Peterson says she barely remembers him gone because he was always present for what was important.

Having a wife who knew what she wanted and held him accountable to the life he dreamed of made all the difference as well.

“Most of my normalcy probably comes from her,” Poppa said, pointing at Grandma who sat with her legs crossed by the window. “She’s kind of been the rock of the family, not me.”

Grandma blushed at this comment. From her smile emanated an aura of pride, and from her eyes it was clear how much she loved her husband.

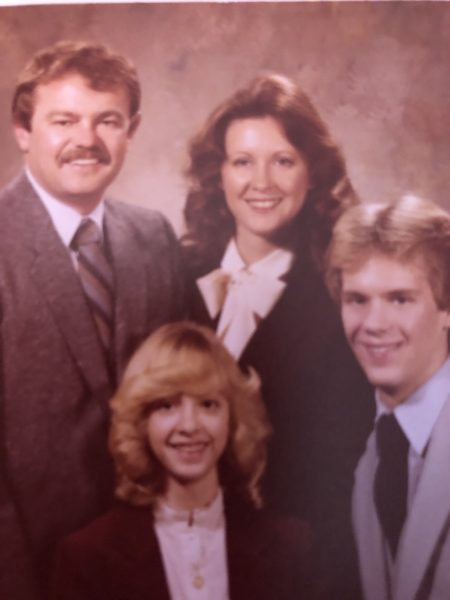

The Reynolds family in 1977 when they lived in West Virginia. Mr. and Mrs. Reynolds are accompanied by their children, Mike Reynolds and Kelly Peterson. Photo courtesy of the Reynolds family.

Though Cavallaro and Mickey had divorced before Reynolds’ children came into the picture, he would still pop in their lives from time to time, trying to convert he and Mrs. Reynolds to the Church of Scientology or making weak attempts to correct his image in Reynolds eyes.

Freddie didn’t allow Cavallaro in his home, and never formed a relationship with his sister. Reynolds, though he never entirely forgave his mother, rekindled whatever relationship they had so she could be involved in his kids’ lives. She died in 1992.

Peterson has pleasant memories with her grandmother, but she was always aware, even as a child, how emotionally detached she was from everyone. When her grandmother would leave town, Peterson knew she might not give one thought about her until the next time she visited. She gives grace to her grandmother though, believing that she was who she was as a result of her rough upbringing and need to persist.

“She was a very strong woman. She felt like she didn’t need anyone else, like she was a survivor,” Peterson said. “When I was in her presence, she was proud and engaged in what I was doing, but she felt like she had to be independent and had to do things on her own, so it was hard to get close to her.” Almost to a point of fault, she might have wanted her kids and grandkids to be the same way.

“She was cold but generous too, her generosity was the way she showed love,” she continued.

As his kids grew older and after multiple successes at work, Reynolds realized a life he never imagined possible. He got a job in the mining industry, making drill bits. The Reynolds family moved to West Virginia and picked up hobbies like snow skiing.

“The four of us took lessons, then we bought a condo!” Mrs. Reynolds laughed.

“We thought, ‘What can we buy in this ski lodge? Hey, why don’t we buy one of these houses,’” Reynolds continued.

Eventually his job moved him to Tucson, Arizona, where he resides with his wife and lives near his family today.

Poppa sat silent for a moment and my grandma watched him, waiting for him to speak again. Grandma’s eyes now looked at him with tenderness.

Based on the way she intently leaned in towards my poppa while he told his stories, I could tell there was a good deal said that she was hearing for the very first time.

“A lot of this I vaguely knew,” she said. “But some of these details… I didn’t know it was that bad.”

“Something I don’t think my mother realized about Freddie and me- we both made successes of our lives. The biggest success we had is we got both our kids through college; Freddie did the same. Both of his kids have master’s degrees. That’s an accomplishment for people like he and I who basically have high school,” my poppa said, shaking his leg. “She was proud of the kids, but never gave any credit to him or me.”

Grandma looked at him, holding her head in her hand and nodding in her chair.

As I picked up my phone, keys, and all the food they were sending home with me, I thanked my poppa for opening up to me and agreeing to do this interview.

I kissed my grandma and poppa on the cheek goodbye and told them I’d see them next week to help make Grandma’s famous chocolate whoopie pies that she calls “Gobs.” As I started walking out the door, I saw my poppa about to say one last thing.

“Oh no, you’ll have to come back sooner than that to get the rest of the story,” he said, “That was only chapter one.”

The Reynolds/Peterson family vacationing in Rocky Point, Mexico in January of 2020. From left to right: Emma Peterson, Isabella Peterson, Kurt Peterson, Kelly Reynolds-Peterson, Ken Reynolds, Donna Hames-Reynolds, Jared Peterson.