By Hayat AlQattan/Arizona Sonora News

The kettle whistles on the stove, in a small white kitchen with white tile floors to match while Sumanpreet Dosanjh rushes around the kitchen, trying to make her dirty chai, pack her book bag, submit her latest assignment and eat breakfast simultaneously.

She runs frantically around like she’s trying to beat rush hour after missing her alarm. In reality, she lives a block away from the University of Arizona and just fell victim to sleep-in syndrome.

She’s pacing around in booty shorts and an oversized blue shirt with a big “A” emblazoned on her chest. The aroma of chai tea reminds her of home; she inhales the rich scent with a nostalgic look in her eyes, “No, it’s not as good as my grandma makes it, I honestly don’t do it justice at all … Mine just seems like a knock-off American version of chai,” she laughs, “but I try my best to get a little taste of home.”

She calls her apartment her “treehouse.” When I ask her where home is, she shrugs, and says, “Home’s here, home’s Phoenix, home’s Flagstaff and home is a small village in the ‘burbs of Punjab.” Dosanjh is a girl who lives with one foot 8,033 miles away in Northern India hugging the border of Pakistan, and another in Arizona.

Dosanjh is 22 years old, a child of Indian immigrants from a remote village in Punjab. Her parents didn’t have an ordinary love story; they met through an arranged marriage. Like many in different cultures, husband and wife met on their wedding day and were expected to start a life together from scratch.

Jatinder, Dosanjh’s mother, was an eligible bachelorette looking to settle down. Upon whispers that ran through her family and across the village, she was arranged to be married to a man with a similar background, Dosanjh’s father, Davinder.

They were not allowed to date, yet could only see a picture of one another and rely on the kind words of whoever roamed in their respective inner circles. They had laid eyes on each other for the first time on their wedding day. Think of it as a blind date, but instead, it’s a blind marriage.

Dosanjh was born into Western culture, her perspective in life shaped by her friends, pop culture, and the media. When she was little, her path still malleable, she was molded everyday by what she saw on the outside, and immediately torn by how she was raised in her home.

Although dating continued to remain a taboo topic in her household, she had an unspoken understanding that some traditions were better left in India.

“I personally don’t ever see myself in an arranged marriage because I’m someone who really needs to get to know someone and know that there is love,” says Dosanjh. “I want there to be not only love but romance and commitment to one another.”

Mr. and Mrs. Dosanjh were very practical about their marriage; they wanted to start a family, they wanted to be financially stable and had big hopes for their children. They believed in the American dream, migrating to a new world so that their children would be raised with opportunities far beyond their own wildest dreams growing up in India. So they decided to leave their Third World nest and fly into a modern world, the United States.

“I would say probably it was the hardest thing they’ve ever done,” says Dosanjh.

After settling in Flagstaff in 1997, they welcomed little Sumanpreet into the world. Her name means “flower princess.” She is their pride and joy. Her mom was overjoyed for a female addition to an all-boy family.

In her early years, Dosanjh spent almost all of her time at home. Her house echoed Punjabi Sikh channels that played on TV. It smelled of home-cooked food like aloo saag biryani and naan and roti which brought the family together on the dinner table.

Dosanjh spoke her native Punjabi with her parents. She was also raised by her grandparents who moved to America with them, and didn’t know a lick of English. Her grandma woke up every morning and made her chai, swirling it with a mixture of spices with flavors so intense it seemed as if it was picked off the local markets of Punjab.

Kneeling on her bed, Dosanjh reaches over her bed frame and traces over single square photos hung in her room wall—a random assembly of memories amounting to more than a decade. Her photographs are a visual piece of home and identity, like her grandfather in his turban; her grandmother in a sari and a headscarf at her high school graduation; the first time she held her nephew. It’s funny how despite being born here, she still experiences a lingering feeling of estrangement when it comes to culture and tradition.

Starting a new life in a foreign land is difficult in its own right: new customs, new culture, new language, new ways of living. For people who look different it only got harder, especially after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

“What really bothered me was going to Safeway with my grandfather who wears a turban and getting hateful words said to him in English,” Dosanjh recalls. “He couldn’t understand, but I did and that hurt me more than anything that could’ve been said to me. He doesn’t speak the language, he doesn’t know any better … It broke my heart.”

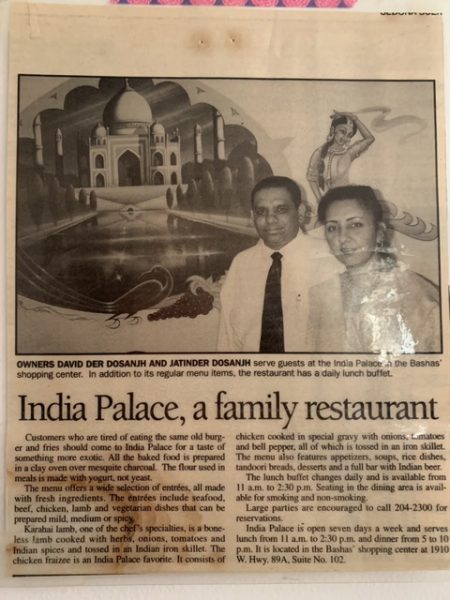

Dosanjh traces over a newspaper cutout of the headline: “India Palace, a family restaurant.” Her dad unfortunately passed shortly after she was born. Mr. and Mrs. Dosanjh had successfully pursued their American dream by migrating to America, raising their children in charter schools and opening their restaurant.

“I’m pretty sure they opened it around 1990. It was dad’s greatest achievement, he was very proud,” says Dosanjh.

She always made sure to go back to Phoenix as much as she could to help her mother out at the restaurant. Mrs. Dosanjh, now a single mother, has had an unfortunate twist to her story when she lost her husband. What was once a shared dream had turned into something she had to do on her own.

No immigrant is without struggle, and with two elderly parents to take care of, a business, and three kids to put through college, Mrs. Dosanjh has perpetually been on her feet, working for over a decade.

Dosanjh saw work ethic, willpower, determination and strength in her mother. Now she is studying to be a doctor, and on weekends she spends her time working alongside her mother. The restaurant is running to this day with great success and she couldn’t be happier in preserving her father’s legacy.

The pictures above her bed are a physical representation of her double life. Some whisper tales in Punjabi and others speak slurs of stories from college nights with friends. The distinction between the pictures is almost night and day, tame and wild. In some, she is Sumanpreet Kaur (as her family calls her) and in others, she is Sumi (as she’s known by her friends at school).

The double life wasn’t always there. In her pre-teen years, she still carried her culture in her looks. Dosanjh was expected to have a certain look under her Sikh religion: women and boys needed to have their hair up, and women had to keep their clothes below their knees. Her brothers wore turbans that wrapped around their Rapunzel hair, dropping to their lower backs.

That was her normal. She never felt any different from the community she grew up in. Even though Flagstaff is a predominantly white community, she was too young to be aware of her appearance, or the color of her skin. She was just the brown-skinned American girl with Indian parents.

As she grew up she saw her reality in a different picture. Her parents decided to move to Phoenix, and she was enrolled in a new school. With a fairly diverse student body, she suddenly became aware of a daunting reality: she was too brown to the white kids and too white for the brown kids.

Despite being born on American soil and carrying that pride that the white kids so proudly represent in their fair skin, Dosanjh still had moments of feeling like an outcast. It’s a lonely, when your identity is two halves of two wildly different worlds.

“There have been instances on the school bus in middle school when people would assume that like, ‘Oh, you’re Osama Bin Laden’s daughter,’ and that would be said out loud in front of people,” she recalls.

She often wondered why she couldn’t be both. Why did she need to choose? She couldn’t bear abandoning her Punjabi roots that she held dear to her heart. She couldn’t completely claim herself to be onlyAmerican because that would mean she would nullify her parents’ and her family’s history.

Dosanjh didn’t feel the need to choose between the two. Instead she has taken the beautiful aspects from both cultures and has shaped her life through them. Like former president Harry Truman once said, “two halves of the same walnut.”

She wants an Indian traditional wedding, but she wants it with the man she loves rather than the man she is arranged to marry.

Dosanjh attends the University of Arizona in Tucson and has her fair share of fun away from home, yet still goes back to Phoenix and helps out in her temple. The balance of the two worlds has shaped her into the person that she is today, and although the struggle remains, she had decided to make the best of it.

“I am, who I am and I am not going to apologize for it,” she says. “Not to myself, not to my family and not to anyone out there who has a problem with it.”