By Jacqueline Canett / El Inde

Mariana Valencia remembers the day she got the best news any person on the lung transplant waitlist could receive.

She was on the phone with one of her best friends when an anonymous phone number called from area code “720” — Denver. She answered the phone and heard, “Hey, we might have some new lungs for you.”

Mariana was in shock. No words came out of her mouth. She described it as ‘such a weird feeling’ but decided to take the news in, get where she needed to be, and then freak out later.

After 26 days on the transplant list and 27 years of suffering from cystic fibrosis — Mariana finally had lungs.

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic life-threatening disorder that damages the lungs and digestive system, affecting the cells that produce mucus, sweat, and digestive juices. The disorder makes it difficult to gain weight and creates lung infections. In 1959, people with cystic fibrosis might only live to 6 months old and as of today, there is still no cure.

The lung specialist at University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora, Colorado, had told Valencia that it was going to be hard to find a match because she is a petite woman. But in the end, even her doctor was surprised her new lungs came in so fast. He ran her name multiple times because he could not believe it was a match.

The hospital proceeded to give her all of the instructions and COVID-19 guidelines. Due to the pandemic, her family was not allowed to be with her during the surgery.

On August 26, 2020, the doctors told her she might not see her mom again, because a lung transplant has a 50% survival rate. Yet all she could think about was her donor: about what an amazing thing they had done, about their family, their friends. Nothing else came to mind and she started praying for them.

To this day, Mariana doesn’t know who her donor was. To her, they were special people that will always be a part of her — literally. To this day, Valencia prays for her donors, their family and friends frequently.

She doesn’t want a relationship with the donor’s family but is eternally grateful. “They’re the weirdest kind of strangers,” she said. She constantly tells people to keep them in their thoughts, as well as the impact a donor can make. Even though an organ donor is going through their darkest time, on the verge of death, they’re giving other people waiting for organs hope. It’s something you can’t put words, a price tag, anything. It’s an incredible gift.

The process of getting onto that donor list is mentally, physically and emotionally exhausting. Mariana ended up with bruises from all of the tests on her forearm, and couldn’t move it from the excruciating pain she was in. She spent weeks in evaluation, getting various X-rays and CT-scans done. She was on oxygen before her surgery, due to her cystic fibrosis, so walking, talking, any simple day-to-day activities were exhausting.

Mariana grew up in the small city of Nogales, Arizona, where she had a very happy childhood. Aside from missing some school during flu season, Valencia was involved in sports and played basketball. She was always outside like any other child but remembers going regularly for chest physiotherapy, and medication.

She never saw a hospital until she was 11 or 12, when she was diagnosed with liver failure caused by her cystic fibrosis. She cried a lot when the doctors told her she needed to stop playing basketball.

She would end up becoming the first person with cystic fibrosis at the Children’s Hospital in Denver to receive a liver transplant in October 2002.

By 2016, Mariana’s health was declining. She was experiencing acid reflux which her lungs were aspirating; E. coli also appeared in her lungs and doctors were unable to stop it. Valencia went in for surgery but the damage had already been done.

She remembers coming out of surgery knowing something was very wrong. Nurses would walk by saying it was part of the recovery and the surgery team said it was the pain medications. But overall, Mariana’s concerns were ignored until her cystic fibrosis doctor came in and listened to her, then proceeded with an X-Ray.

She was diagnosed with pneumonia. It hurt to take a deep breath because of the scars she had. At this moment she thought it was the end, when tears started running down her face.

She could not eat solid foods as part of her recovery from her liver surgery and only had enough nutrients to breathe. This went on for a month, until her doctors recommended a lung transplant — a 12-hour surgery. The lung transplant was a gamble: If the donor’s lungs collapsed, then she would have to go through surgery without a new pair of lungs.

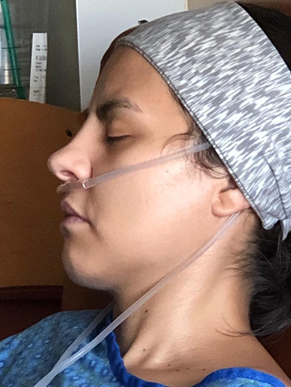

Photo courtesy of Mariana Valencia.

Mariana remembers waking up, feeling tubes everywhere alongside the scar in her chest from where the doctors had opened her up. ‘What if these are still my lungs?’ she asked herself. So, she took her first breath, a crisp smooth grasp of air. That is when she knew the surgery was successful. The air smoothly left her lungs and nothing blocked her airway; it was so easy to breathe. So effortless. So essential for everyone. So automatic. Mariana remembers crying a lot the first day because she had not been able to breathe, laugh or do other everyday activities without going into a coughing fit. For years, she had stopped laughing and learned how to control her breathing.

She remembers the first person she saw after surgery was her dad. Then, on the following day, she saw her brother Gabriel. After that, she was her mom.

Two days after the surgery, Mariana sat down for the first time with her new lungs. She had been on a hospital bed most of her life and just wanted to get out of there, so she started walking four days after her surgery. And today, months after surgery, every time she exercises she finds it weird how her body gets tired before her lungs do.

Photo courtesy of Mariana Valencia.